Happy New Year, everyone! I hope the kickoff to 2022 is finding you safe, warm, and well. Like many of you, I’ve been trying to wrap up a number of projects toward the year’s end, so first, a bit of catching up in the world of local development, where a lot has happened over the past six weeks—here are just a few highlights (with links):

On November 12, ProPublica reporter Anjeanette Damon published a long and deeply-researched article about Jacobs Entertainment and the City of Reno called “He Tore Down Motels Where Poor Residents Lived During a Housing Crisis. City Leaders Did Nothing.”

On November 19, Scenic Nevada filed a lawsuit against the City of Reno over the City’s Development Agreement with Jacobs. More on that here.

On December 11, Damon hosted a panel on affordable housing with representation from the City as well as “an affordable housing developer, an outreach worker who lived outside for 10 years, a housing justice activist, a housing policy advisor, and a lawyer for Jacobs Entertainment developers”—you can read her recap and watch the video here.

The City has scheduled a public meeting on January 10 to discuss its finalized Development Agreement with Jacobs and the company’s future plans.

We’ve also had a glimpse of more proposed actions coming down the road:

In January, Jacobs Entertainment will be requesting two sets of street/alley abandonments in the vicinity of Church Lane and West 2nd Streets, and Ralston and West 5th Streets (they were removed from the December 8 agenda).

Jacobs applied for a demo permit for the Nelson Building at 401 West 2nd Street and demolished the 7/11 Motor Lodge, raising concerns for the adjacent historic Gibson Apartments and its tenants.

The City may consider selling the Community Assistance Center buildings on Record Street, another item that was pulled from the December 8 Council meeting after the community raised concerns about available shelter space.

CAI Investments (the company converting the Harrah’s Reno property into Reno City Center) applied for a permit to construct a skyway over Commercial Row to link their building to the Whitney Peak parking garage. That proposal was reviewed by the Skyway Design Review Committee on December 13 and will next be reviewed by the Planning Commission (date TBD).

I’ll give some of these upcoming decisions more attention as they get closer, but in the meantime, I want to take a step back and talk about what lies behind the concerns I’ve had with some of the development projects and proposals that have come along this past year. In the end, it all boils down to one question: “Where are the people?”

I don’t mean that just rhetorically. In my last Brief, “Public Process in Crisis,” I raised concerns about key decisions being made about the form, function, and naming of some of our most central public spaces and places without the direct and deliberate involvement of the people, the city’s own residents. (I’ll have more to say about some of those specific actions and their repercussions in a future Brief.)

Why does that constitute a crisis? Because it’s the job of a representative government to secure the broadest possible benefit from the decisions they make. And there’s a very real, very concrete reason why deliberately seeking out the perspectives, knowledge, and experience of the citizenry is so crucial when it comes to shaping the built environment we share: if you don’t, you may very well end up creating places where most of your citizens will never want to go. And Reno can’t afford to do that any longer.

Lessons from the Hof Brau

Sometimes when people (myself included!) talk about cityscapes, we can get a bit carried away with technical analysis, narrowing in on things like “walkability” and “pedestrian scale development.” But what we really have to keep at the forefront, more than anything, is how people actually relate to and move through communities, how we think and feel about places. What draws us to a neighborhood or district or downtown? And what makes us fall in love with it?

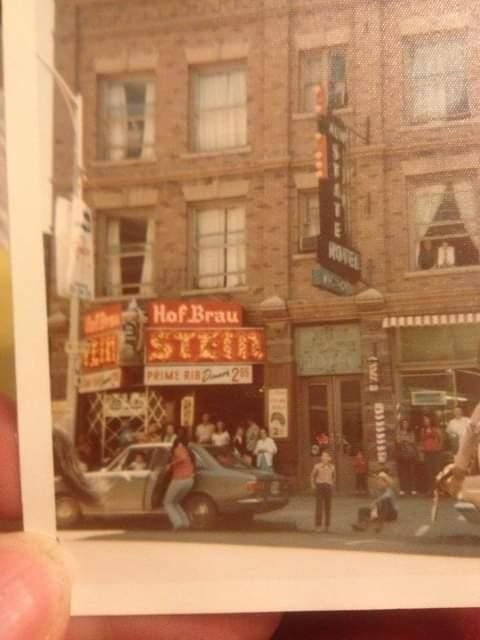

Through the website I edit, Reno Historical, I’m often sent queries about Reno’s historic places, and a few days ago, someone wrote for help remembering the name of a cafeteria-style restaurant on Center Street where they used to eat in the 1980s. I did a quick search of city directories and came up with Stein Hof Brau, a smorgasbord-style German restaurant on the ground floor of a three-story hotel, between First and Second Streets. I’ve studied Reno for a long time, but I’d never heard of it.

Intrigued, I posted a question about it to the Facebook page called “You lived in Reno in the 60s and 70s if you remember…” and was rewarded with a flood of personal memories—80 people commenting in the first 24 hours, and 132 within four days. Someone posted a photo they’d found online years before. People remembered the luscious French dip and hot turkey sandwiches and freshly cut prime rib. They reminisced about the aromas and the ambience. But what really struck me was how they remembered the Hof Brau in relation to the larger downtown community. They remembered walking over for lunch from their jobs at one of the nearby banks, the Nevada Bell building around the corner, the Riverside Hotel’s Flower Shop, the County Court House, Harrah’s, and Don’s Drugs, just a few doors down.

They recalled gathering at the Hof Brau for meetings of the Dial Club, the Sigma Nu Alumni, the Sons of Erin, and the Geological Society of Nevada. They reminisced about spotting Reno’s movers and shakers there—bankers, attorneys, business leaders, and reporters from the newspaper offices across the street. They remembered stopping in after getting a haircut from Dutch Myers at the barbershop next door, or before catching a movie at the Majestic Theater on First Street. They remembered vitality. They remembered life. And they remembered loving their downtown.

Some deride nostalgia as undue attachment to the past that keeps people from moving forward or accepting change. And if what you’re nostalgic about are outdated values best left in the past, that may be true. But nostalgia can be a glorious gift, immensely valuable not just for the way it populates our minds with warmth and affection, but for its ability to remind us what we loved about places from our past, and to teach us how we might inspire that same lasting attachment to the places we create today.

I never had a chance to visit the Hof Brau, but I can fully grasp how it contributed to a vibrant community. Generations ago, downtown Reno was brimming with people, thanks to places like the Hof Brau and the ecosystem it was a part of—the theater, the banks, the newspaper offices, the barber shop and the hotel rooms above it, the clerks and power brokers and families walking in and out and all around.

It’s the story told by many cities, where, over time, many traditional storefronts with rooms or offices above were gradually replaced by bigger buildings—skyscrapers and office buildings and malls and civic centers. But Reno’s story veered off in a very particular direction, embracing urban forms and patterns that were vastly different from other places and that have made its revitalization much more challenging.

Instead of a mix of businesses and services at street level, the casinos that started to replace many of Reno’s downtown storefronts opened up to huge gaming floors. In the next phase, a wave of hotel casinos nestled their restaurants and gaming floors and showrooms even further inside and away from the street. As some found success, others followed their lead, and in the process tore apart more of that urban fabric, the bank, the flower shop, the offices and movie theaters. The focus became auto tourists, not pedestrians. The building that housed the Hof Brau and the barbershop was razed and replaced by a second parking garage for the Cal-Neva. A skybridge was constructed to connect it to the casino, mirroring the one constructed to connect Harrah’s to its own parking garage, just up Center Street.

And when that new downtown was in full swing, 24/7, it was indeed bustling with activity, as an amateur video from 1992 shows. There was no need for a diversity of uses when gaming brought in a steady stream of people, as well as a steady stream of cars, and the parking garages and skyways multiplied to cater to them.

It worked well, that is, until it didn’t. We all know the story. As the casinos closed, one after another, those spaces were not easily readapted into the contours of a regular, functional downtown, something Mike Van Houten explored a few months ago in a terrific piece called “Downtown Reno's Conversion Projects: What works and what doesn't.” And as he pointed out, there’s a lot that still doesn’t.

As a result, the main question people have asked when visiting Reno over the past two decades or so is the same question I’ve been asking:

“Where are the people?”

There is no quick fix for bringing more physical activity back to the sidewalks and spaces of downtown Reno. It can only happen through committed, ongoing, cumulative efforts on all fronts, efforts like these:

Restoring the number of smaller storefronts with a variety of businesses.

Building in a mix of attractions, experiences, and amenities for the widest possible cross-section of people to experience at all times of the day, every day.

Replacing single-use parking garages and surface parking lots with parking facilities that contain ground floor commercial space and even outdoor seating, like the Parking Gallery at First and Sierra Streets—-and encouraging residential developments that contain internal parking to do the same.

Eliminating long stretches of building-free dead space, which leave passing pedestrians isolated and vulnerable.

Discouraging the construction of new skyways and pedestrian bridges that keep people off the sidewalks.

Designing human-scale public spaces specifically to bring people of all backgrounds, ages, and abilities together and give them reasons (and the physical means) to linger, throughout the day, every day.

Much of a city is private property controlled by private entities, but the public—through our government—does get ample opportunities to influence what happens there by formulating policy, reviewing specific projects, and designing public spaces that welcome and work for everyone.

And city governments have to balance a lot of goals, values, and priorities when making those decisions, things like making the city safe and beautiful, promoting and attracting investment, improving its image, and generating revenue. But when facing every decision about downtown Reno in particular I think we have to always start and finish by asking, “How would this choice help to bring the broadest possible cross-section of people to this place? Are we doing everything we can to make that happen?”

Now I know that some might say that no single action can accomplish everything, and that’s true. But think about it. Generating more foot traffic in our downtown doesn’t just promote all the rest of those goals; it’s actually impossible to accomplish most of them without it. And it isn’t a natural byproduct of the others, either. In fact, it’s very possible for decisions made in focused pursuit of one or more of those other goals to actually discourage foot traffic, inadvertently hindering the very vitality we seek.

There are so many resources to help us think through how this can work, because the solutions are well known and practiced elsewhere all the time. The Congress for New Urbanism, for instance, has focused for decades on helping cities build around people, not cars, prioritizing equity and sustainability. The Project for Public Spaces is the leading authority on creating public spaces that strengthen communities. The Incremental Development Alliance helps cities and citizens build places people love.

If we don’t consistently prioritize ways to increase the pedestrian use of downtown Reno, if we keep missing opportunity after opportunity to do that, then before we know it, all the opportunities to do it will be gone, and we will have ended up not changing anything and then wondering why we still have a problem.

We are at a critical juncture here, as private investment in downtown accelerates, promising rapid and potentially irreversible transformations. And what we do now from a civic perspective—private property owners and developers, government and residents, all working together—will determine whether downtown Reno can achieve its full potential and again become a place brimming with life and vitality.

And that’s why examining the repercussions of various actions, understanding how cities work, and appreciating how people relate to places is so important for all of us. Some choices will get us to a place where we need to go, and others will not. And I think we need to do everything we can to tip the balance in the favor of the former.

Looking for People in the “Neon Line District”

I’ve devoted a lot of space over the past year to discussing actions related to Jacobs Entertainment, and it should be pretty clear why: any entity that controls that much land in the heart of downtown has an unsurpassed ability to singlehandedly determine the future of the area they control, potentially for generations to come.

And let me be clear: It’s perfectly natural for a private company to pursue its own interests, in development as in anything else. But it would be naïve to assume (and disingenuous to suggest) that the private interest of a company (particularly a for-profit one) pursuing its own private goals is always going to match the public interest. It’s the job of the lobbyists and representatives of that company to persuade public entities that they do align, but that’s simply not always the case. That’s just a fact, not a moral judgment. There should always be a counterpoint to the confident assertions made by those representing private interests, and that’s where the people need to step in and ask, “What about us?”

As I’ve noted before, the Development Agreement that the City finalized with Jacobs in October left largely underutilized the City’s ability to set requirements for amounts and types of housing (to address the City’s serious housing shortage), timelines of construction (to fill in vacant lots), detailed procedures for treating specific historic properties (like the Nystrom House, still vacant and endangered), and many other considerations that could have helped to ensure that the company’s activities and actions would provide substantial, specific, and speedy community benefit.

With the staggering number of parcels they bought, Jacobs could have put together an overarching master plan that would have transformed this part of town into the walkable, bustling neighborhood we’ve wanted the heart of downtown to become once again—and our elected officials were understandably enticed and enthused by the prospect. But Jacobs didn’t do that. There is no master plan.

And the enormous missed opportunity here is that the City didn’t require them to provide one in return for everything they were requesting. Despite the massive large-scale revitalization of the area being touted, this agreement did not establish any parameters to ensure street-level activation of any of it or to lay out even the most basic plan for how the elements of this new ecosystem might connect to and complement each other. But that cohesiveness is literally why certain parts of a city become recognized as “districts” in the first place. And as I’ve previously pointed out, the Travel Nevada website is already promoting it that way to tourists:

With a description like that, you’d expect to arrive on West 4th Street and see something like Fremont East in downtown Las Vegas or San Diego’s Gaslamp Quarter. But not only do none of those promised “hotels, retail stores, and restaurants” currently exist along the “Neon Line,” it’s less and less likely that they ever will. Why not? Because there’s nothing requiring anyone to build them.

Where precisely would those new retail, restaurants, and hotels be located? Jacobs just this week submitted a new application to make their “Glow Plaza,” extending from Washington Street eastward toward Ralston Street, a permanent “festival and concert grounds,” with no buildings, just a large parking lot to its east, and other nearby Jacobs-owned parcels remaining open and available for overflow parking. That means the entire south side of Fourth Street between the Gold ‘N Silver and the Sands Regency will remain empty and inactive most of the time. The north side of West 4th through that entire stretch has nothing commercial except the Gold Dust West—it’s all motels and condos and apartments (which I’m in no way advocating be removed or changed, just pointing out that there’s nothing commercial there, either).

Well, what about on the rest of the parcels Jacobs owns? Aside from the corner of Arlington and West Second Street, where they’ve promised to construct condos, the agreement placed no requirements or restrictions on any of it, including on any parcels Jacobs might sell. A buyer may want to include some street-level retail or restaurants on whatever parcels they purchase, but they may not. It’s entirely up to them. (For an example of a public-private partnership carefully designed by a city to guarantee the production of a vibrant place-based urban district, check out how the City of Las Vegas conceived of the Fremont East Entertainment District in 2002.)

The package of fee deferrals and other incentives that the City of Reno granted Jacobs through its Development Agreement are indeed tools the City has used elsewhere to facilitate development, but in other cases, they are granted only when developers are revealing precisely what they plan to build, whether it’s a single building or an entire project like RED, which is physically constructing necessary infrastructure like sewer lines, streets, sidewalks, and the like. Here, as in most infill projects, no new infrastructure is needed, but the lack of specificity regarding what is to be built means that the City of Reno (and Reno residents) have no way of knowing.

And we likely won’t know until they apply for building permits. Development Agreements can’t be used to evade discretionary reviews, but in this case, any properly zoned development won’t require any. Tentative maps, for instance, only require approval when a parcel is to be divided up, as with subdivisions or condos. And Jacobs is hoping to get several street and alleyway abandonments approved prior to the sale of the parcels abutting them, in order to make those assembled parcels more appealing to buyers intent on large-scale development—whatever it ends up being.

So if the agreement with Jacobs did not guarantee a revitalized and lively urban district, what did it provide that wouldn’t have occurred if Jacobs had just bought and sold its parcels without one? That’s where the agreement worked entirely in Jacobs’ favor, giving the company the right to designate and define a huge amount of land that it does not own, including the private property of others, public space, and a major primary thoroughfare, under its own independently-conceived brand of the “Neon Line District.”

In giving this territorial claim their official seal of approval, the City has condoned the creation of a completely new type of district: one that places a single company in complete control of an entire area’s branding, appearance, and marketing—allowing them to extend their privately-selected brand into public (and others’ private) space. (That public-private slippage is, in part, the subject of Scenic Nevada’s lawsuit.)

Together, the district’s name, the sculptures, the glitzy LED-lit wall spanning five city blocks, the proposed archway sign over West 4th Street and other signage along Keystone and Interstate 80 collectively link and market the Gold Dust West and Sands Regency, as well as the “Glow Plaza” between them, as a single Vegas-size entertainment destination benefiting one entity: Jacobs Entertainment. And the primary audience for all of that—as made clear by the expansive parking lots, and the signage placed at a location and height for optimal visibility to auto traffic—is not local residents at all, but tourists—and especially, tourists in cars.

In short, it’s the very pattern that we’ve been trying so desperately to reverse in the downtown area. It’s as though the City of Reno decided to make West 4th Street the new, vehicular approach into downtown, without making any attempt to ensure that the corridor itself emerge from the ashes as the revitalized pedestrian-oriented, mixed-use district that was promised. And no, Burning Man sculptures and a LED-lit wall can’t singlehandedly transform blocks of otherwise empty space into a bustling pedestrian district; if they could, that would already have happened. (For a reminder of how part of that stretch looks, view my video taken from a car and the sidewalk.)

As many have pointed out, what this part of downtown could really use is housing, especially housing that is as accessible as possible to a wide cross-section of residents. And there likely will be housing constructed on some of those parcels beyond the condos Jacobs has promised, but only if buyers decide to build it. Would builders be more likely to purchase land and construct housing in an area specifically because it’s been named and promoted as the “Neon Line District”? Not likely. They’re going to buy it because it’s in an Opportunity Zone, because it comes with incentives and fee deferrals attached, and because it won’t require them to submit to any additional reviews for projects that meet the area’s zoning (which, in the Downtown Northwest Quadrant and Downtown Entertainment District, which this land encompasses, provides a lot of options). The “Neon Line” brand is all for Jacobs.

The January 10 Community Meeting on the Neon Line

With the Development Agreement already finalized, can anything be done to steer the ship back in a more resident-oriented direction, one that absorbs the lessons from the beloved Hof Brau, reverses Reno’s trajectory of catering to autos over pedestrians, and benefits from an understanding of best practices for urban development?

I hope so, and the City’s January 10 meeting, to be held from 5:30-8:00 pm at the National Automobile Museum, although woefully late in coming, provides an important opportunity to voice as many concerns, questions, and requests as possible. The way I see it, there are three basic things that the City and Jacobs can provide at this meeting: explanations of past decisions; information on what concrete plans are underway and envisioned for the future; and identification of what specific opportunities still exist for residents to influence what happens in this area, to ensure that it provides the maximum possible benefit for those who live here.

For instance, here are just a few of my questions. First, for the City of Reno:

If this entire “district” isn’t owned or master-planned by Jacobs Entertainment, then why should this one company be allowed to unilaterally decide what it’s named, what its boundaries are, how it’s marketed, and what its streetscape elements (like streetlights) look like? Shouldn’t a district have members who get to participate in all of those decisions, like the Riverwalk and Midtown?

What exactly does the City consider to be the “public benefit” of this Development Agreement, how was that decided, and by whom? Is the City defining privately-selected and installed sculptures and signage that went through no public process as “public art”?

Is Tax Increment Financing still being considered for this area, and if so, when will that be proposed, and how will the City ensure widespread public participation in discussions about it?

For Jacobs Entertainment:

How exactly do you intend to develop the land that you plan to retain, and when? Do you plan to construct any outward-facing retail, restaurants, or other commercial amenities at street level on any of it, and if so, where?

Will the “Glow Plaza” be the area’s only outdoor concert and festival space?

Do you plan to purchase any more parcels and if so, where, and for what?

What happened to the neon and other signage from the motels you demolished?

What are your specific plans for the historic Nystrom House and when will they be initiated? Are you willing to re-list the house on the City of Reno’s historic register to protect its historical integrity?

You likely have many more questions, concerns, and requests of your own, and the City has encouraged that questions be submitted in advance, so they can incorporate as many responses as possible into their presentation. Don’t forget to register for the meeting, whether you want to attend in person or virtually. And I encourage you to share your thoughts in advance with others, too, on social media or in conversation, to help generate more insights about what you’d like to discuss there. This meeting can only be successful if it becomes a robust conversation that goes beyond what we already know to clarify how development of this area can truly benefit the people.

BRIEF TIP: Register for my talk on the Lear Theater!

I’ll be giving a virtual talk about the architecture, architect Paul Revere Williams, history and current status of the First Church of Christ Scientist, better known as the Lear Theater, on Tuesday, Jan. 11 at 5:30 p.m. The free talk is offered by the Historic Reno Preservation Society, on whose board I serve. You can register in advance for the Zoom stream here. Please join me! [Update: You can access the video by scrolling down to the link on this page: http://historicreno.org/index.php/archives/past-speaker-videos?mibextid=Zxz2cZ]

As always, you can view my previous e-newsletters, with more context, analysis, and tips, on my Substack site and follow the Brief on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. If you’d like to contribute to my efforts, I have a Venmo account at @Dr-Alicia-Barber and would be grateful for your support. Thanks for reading, and Happy New Year!

Why aren't the sites underlined in this document secure when opened in one's computer???? They should not be open to hacking!!! Come on Reno City, get with the times.

Jeff Jacobs is interested in one thing: Jeff Jacobs! He is not and never has been civic minded.