Time to Get Real: Authenticity in Placemaking

Thoughts on Jacobs Entertainment, the Reno Redevelopment Agency, and Reno

This week brings a rare appearance at Reno City Council by representatives (or at least one, anyway) of Jacobs Entertainment. Two items on the agenda of the Reno City Council for Wednesday, October 22nd are basically check-ins on two documents: the conditional use permit for the Glow Plaza & Festival Area (not to be confused with the newer “Festival Grounds”) and Jacobs’ overall Development Agreement with the City:

Item C.5. Staff Report (For Possible Action): Presentation and status update on the Jacobs Glow Plaza & Festival Area Conditional Use Permit (LDC22-00038 & amendment LDC23-00032) in accordance with adopted conditions of approval for annual report to City Council on the project’s operations. Staff report here.

Item C.6. Staff Report (For Possible Action) Presentation by Developer of the status report regarding the Neon Line District Development Agreement. Staff report here.

The check-in on the Glow Plaza is an annual report, while the Development Agreement only requires reporting every two years. So if you have anything to say about either one (say, about the level of noise generated by the Glow Plaza, one of the most generous allowances of its conditional use permit), this is your last chance to do so (at least with a Jacobs audience and a Council action item) for a while.

You can read a full preview of the Council agenda from This is Reno here.

There’s also an action item on Wednesday’s agenda of the Redevelopment Agency Board (also the members of Reno City Council) about rebranding the Redevelopment Agency to incorporate the notion of placemaking, among other things (it’s Item B.2 with the Staff report here).

Again, one of the listed attachments—this time, the presentation—is not actually included, so if you want to offer your own advance opinion on which (if any) rebranding option the City should choose, you’d appear to be out of luck. (Seriously, why does this absence of listed attachments keep happening?) Fortunately, in this case, Mike Van Houten of Downtown Makeover (who serves on the Redevelopment Agency Advisory Board) has provided his own preview here.

Both of these topics have me thinking a lot about how people connect to places, the focus of much of my professional work as a public historian. It’s also on my mind since I recently led one of my two-hour historical walking tours of downtown Reno. There’s nothing like walking around downtown to give a person clarity on what it takes to truly “make” a place and how easy it is to mismanage or even to destroy it.

I’ll get back to Jacobs Entertainment and the Redevelopment Agency rebranding in a moment. But first, as prelude, I’d like to share a few thoughts on place identity—because ultimately this isn’t about branding or permitting—it’s about you, here, now.

The Three Components of Place Identity

The inspiration for my book, Reno’s Big Gamble, came from Reno’s well-publicized identity crisis that began in earnest in the 1990s. City leaders were publicly asking what would and could Reno possibly be, now that dozens of casino closures had tarnished its formerly solid status as a bustling and successful gaming mecca. When I researched the history of decisions about the development of Reno’s downtown area in particular, they seemed driven repeatedly by promises of momentary economic gain rather than some kind of long-range, coordinated vision. That was the “big gamble.”

Increasingly, in the 1990s, many Reno residents did not frequent or even like their own downtown; city promoters did not know how to sell it; and outside entities (from Reno 911! to the Muppets) made fun of it or even outright derided it.

That’s three different entities—residents, promoters, and outsiders—with negative, or at the very least, unsettled, notions of what downtown Reno was and could be.

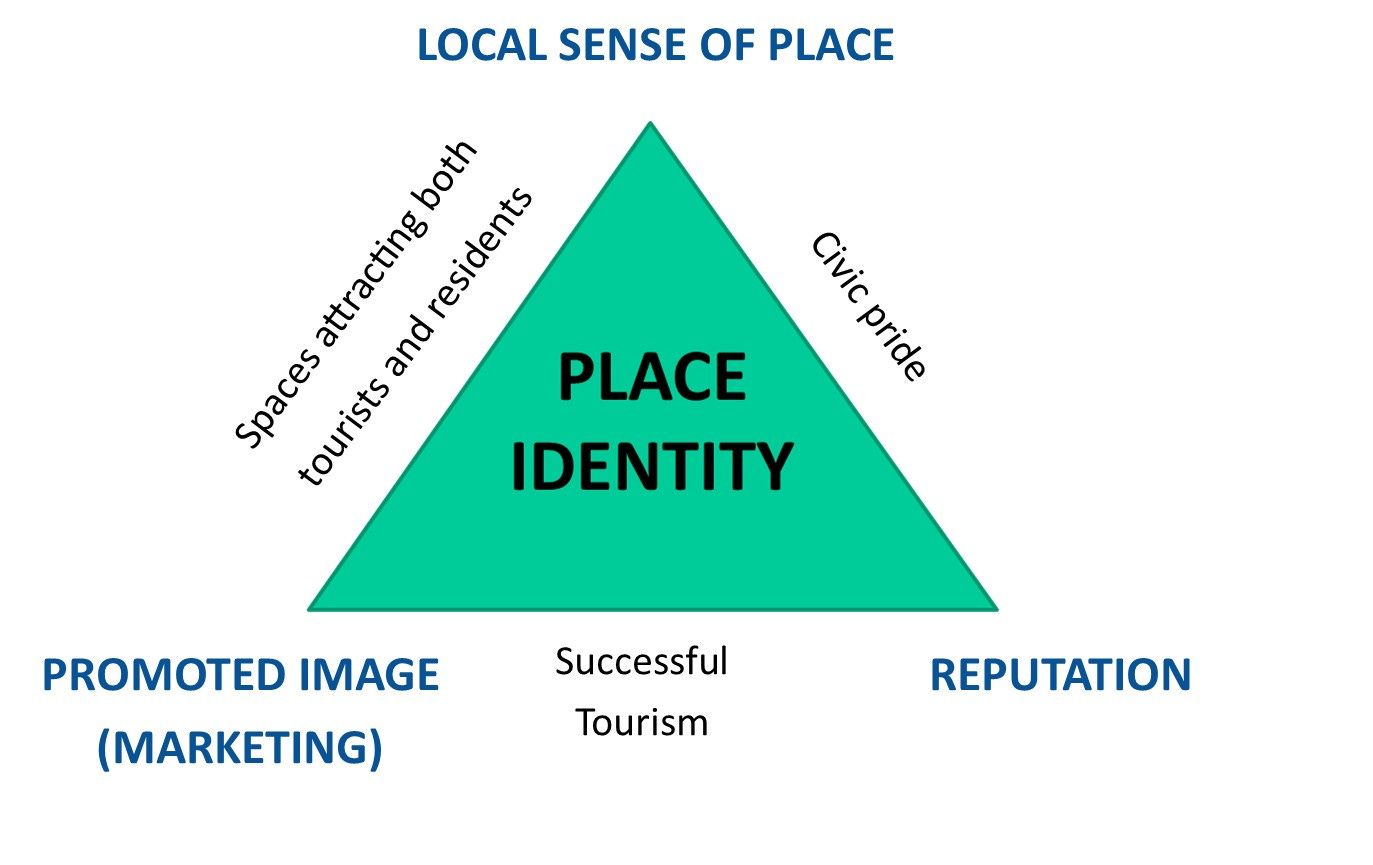

In my book, I suggested that these three different groups of people were responsible for the three aspects of the identity of downtown Reno or, indeed, of any other city: the residents’ sense of place; the place’s promoted image; and its reputation.

When all three are positive (residents love it, marketers have something positive to sell, and outsiders agree with both of them), a place enjoys an aligned and harmonious identity. Here’s a graphic to illustrate that ideal relationship.

Looking on the left side of the triangle, you can see that when the promoted image and local sense of place are in alignment, the place attracts both residents and tourists—the ultimate goal of urban tourism. Tourists, after all, want to experience cities as its residents do, craving an authentic taste of what makes a place unique and special.

On the bottom of the triangle, you can see that when the promoted image matches the place’s reputation, place marketers can be assured that they’re on the right track. They’re not trying to sell a place as something it isn’t, and visitors don’t feel misled.

And on the right side, when the local sense of place and the outward reputation align, residents feel a sense of civic pride. They don’t have to defend their place or its reputation from outside opinion, because outsiders love it as much as they do.

You can apply this formula to any size of place—a city, a neighborhood, even a single destination, so long as it’s hoping to earn the affection, loyalty, and patronage of both residents and tourists—as every place that’s not an isolated resort should strive to do.

When any one of these components is out of whack, you start to see problems, and it generally begins when a place falls into decline. As I wrote in my book:

Economic and aesthetic decline, when witnessed by visitors, can cause a city’s reputation to plummet. A negative reputation, in turn, can affect investment and visitation, thereby contributing to the deterioration of the landscape, which is likely to damage the reputation further, and so on. In the worst-case scenario, this produces a vicious cycle whereby the battered landscape and reputation together spur an endless downward spiral.

A lot has changed in downtown Reno over the past 25 to 30 years, but this basic dynamic holds true. These three factors of place identity can lift each other up, or they can drag each other down. But the key to solving all of it is the authentic connection of people to place—the precious relationship at the heart of true placemaking.

The Touchstone: Residential Sense of Place

Places oriented primarily toward tourism can tend to downplay the importance of residential sense of place to their overall identity, not recognizing its critical importance to their ultimate success. Residents, after all, aren’t their target audience; they crave those outside visitors and their money and want their heads in their beds.

That outsiders-first mentality shaped the approaches of most of the larger hotel-casinos and casino resorts built in Nevada from the 1970s onward. They catered primarily to the visitor—and in Reno, to the cars in which those auto tourists primarily arrived. Sprawling surface parking lots, multi-level parking garages, huge glitzy roadside signs, high-rise hotel towers lit up in shades of pink, green, and blue—all beckoned the visitor with promises of convenience, comfort, delectable food and drinks, and nonstop entertainment.

Did residents visit these places, too? Of course. But residents weren’t asked how they should be designed or how they should be marketed. What business ever does that, anyway? Choices of marketing and design are the prerogative of the business owner, for good or ill. The themes they assume are ostensibly the product of intense market research, derived through careful evaluation of the potential to appeal, attract, intrigue, and establish a sense of loyalty. For the casinos of late 20th century Nevada, the sky was the limit, from pyramids to pirate ships. In Reno, thematic choices were more modest and largely interior: a Spanish city of gold, the circus, the glamour of Hollywood, a silver mine, a tropical jungle, a taste of Tuscany, the wild west.

We all know the story. It worked for downtown Reno until, well, it didn’t. Look back at that triumvirate of place identity and you can trace the domino effect of decline, on all fronts. The big question now is not what happened, but how to turn it all around.

The City of Reno appears to recognize that residents are the key to revitalization. When you lose residents, you truly lose the place, and not just because tourism can fluctuate so drastically by season, the state of the economy, and the allure of competition. Residents infuse a place with life. Their constant presence fills streets and spaces with activity. Their visibility constitutes an endorsement of a place as authentic and true. You don’t have to perpetually manufacture special events and artificial reasons to induce residents to frequent a successful area; they simply want to be there because it offers something they want in a landscape that speaks to them.

Which brings us back to Jacobs Entertainment and the potential rebranding of the Reno Redevelopment Agency as a placemaking agent.

The arrival of Jacobs Entertainment in Reno and the City of Reno’s relaunch of its Redevelopment Agency after several decades of dormancy, although separated by a few years, are occupying the same stage of Reno’s attempted downtown revitalization, one where connecting with residents is not just desirable but absolutely essential. But when it comes to cultivating that actual connection, both leave much to be desired.

Jacobs Entertainment and Downtown Reno

Jacobs Entertainment is not coming to City Council on Wednesday for a review of its overall business operations or its brand. As I’ve extensively documented, the City’s Development Agreement with Jacobs regarding what it is currently calling “Reno’s Neon Line” actually requires very little from the company. You can get a general sense of my disappointment about that in my Brief from October 23, 2021 titled “City Council’s Baffling Approval of the Jacobs Development Agreement.”

Read through the Staff Report on the Development Agreement, and you’ll see just how little the company actually needs to document or do. Barring the announcement of some new “milestone” or plan (which is the company’s established pattern on days when they appear in front of City Council), it could take about ten minutes to review.

(By the way, if the conditional use permit for the Glow Plaza and Festival Area interests you, I wrote about that several times including in my May 24, 2022 Brief titled “DeBrief: The Glow Plaza and Festival Area Appeal.”)

Thankfully, and in contradiction with the formal development name on the legal agreement, the company is no longer trying to sell its neon-tinted, LED-lit resort as a “district.” (Its initial attempt to do so, which I wrote about here, evoked the classic “Coffee Talk” sketch from Saturday Night Live, where Mike Meyer’s Linda Richman character, temporarily “verklempt,” might instruct her audience, “Talk amongst yourselves. I’ll give you a topic. The Neon Line District is neither neon nor a district. Discuss.”)

They are, however, still trying to sell themselves as the hotbed of neon. That authenticity deficit, demonstrated most markedly by the company’s assertion that the dozen-plus midcentury motels that it demolished held no value beyond inspiration for its overall brand, is reinforced further by the company’s current assertion that they are in fact responsible for bringing neon to Reno for the very first time.

A successful brand should be eye-catching and intriguing, but it must at the same time be true. And that’s even more important when purporting to represent the actual history of an authentic place and connect to people through that theme.

(If you want to learn more about Reno’s actual relationship with neon and the signs that authentically tell that story, please follow and support The Light Circus as it prepares to open in the National Bowling Stadium early next year. And if you want to see what authentic districts are all about, be sure to check out MidTown, the Riverwalk, Wells Avenue, and the Brewery District.)

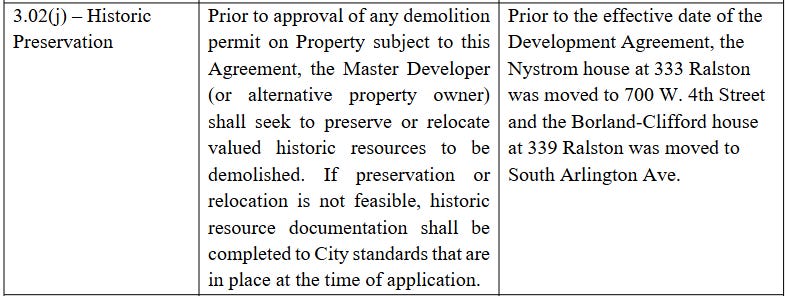

Getting real about history means getting real about historic preservation, too. Under that section in the Jacobs Development Agreement report, we see these lines:

Just as the words “neon” and “district” hold actual meaning, so too does the term “historic preservation,” which means far more than the absence of demolition. This agreement never required the determination by anyone other than Jacobs Entertainment itself that a resource was “historic” or “valued” or if its relocation were “feasible.” Whether documentation of all of the properties the company has demolished was ever completed, or if the City developed any “standards” governing such documentation, I have no idea. The residents of this place would have been better served if they had, and if this section were taken with any degree of seriousness.

Placemaking and the Reno Redevelopment Agency

As Mike Van Houten writes, “The full new name of the Reno Redevelopment Agency will be ‘Reno Redevelopment and Urban Placemaking Agency.’” But when it comes to the desire to strengthen connections of residents to the places and spaces of downtown Reno, the City’s Redevelopment Agency would do well to think about how successful placemaking is accomplished (and how it is not; see above), as well as the degree to which residents themselves should be enlisted to help steer that process.

One of the most striking aspects of the Virginia Street Placemaking Study, for which the City hired an outside consultant, was the extent to which it ultimately boiled down to a pretty generic approach to urban design, disconnected from Reno’s identity, history, and place, with a major emphasis on spaces for special events. That may have been a byproduct of its overall approach. There was no moment when the consultants staked themselves out on Virginia Street and asked passersby how they felt about the street, or how they saw its potential, or if they were residents, what they missed or craved.

There were the ubiquitous online surveys, but there were no surveys, gatherings, or workshops for the study held outside on Virginia Street at all (I attended one inside the historic post office). It was as though the thoughts of the day-to-day users of the street (as evidenced by their actual presence on the street, not for their classification by the City as “stakeholders”) had no bearing, valuable only in the abstract, not in reality.

I had some similar concerns about the relaunch of Reno’s Redevelopment Agency—and specifically how the documents to govern the agency and its operations were put together without any consultation with residents or property owners in the redevelopment areas themselves. (See my October 2024 Brief titled, “ALERT: We need to talk about Reno’s Redevelopment Agency”). Rather, an outside consultant worked directly with City staff to determine how the redevelopment areas would be subdivided, how those subdivisions were described, and what would be listed as desirable additions to each. Those who were already there had nothing to do with it.

That’s not how you develop a sense of place that actually means something to the people who live and work there, or a successful destination for those who visit. If the Reno Redevelopment Agency is going to adopt a new brand that suggests that it is the driver of urban placemaking in Reno, I hope its leaders can articulate specifically what that means to them, and how they intend their actions to strengthen the connections of actual people to this actual place—not just in word but in deed. After all, places are not “made” by the government, or by private companies, or by expensive logos; they are “made” by the people who love them and for whom they mean the most.

You can view this and prior newsletters on my Substack site, subscribe to receive each new edition in your email inbox, and follow the Brief (and contribute to the ongoing conversation) on X, Facebook & Instagram. If you feel inspired to contribute, you may purchase a paid subscription through Substack or contribute via Venmo at @Dr-Alicia-Barber or via check to Alicia Barber at P.O. Box 11955, Reno, NV 89510.

This is amazing. Thank you for synthesizing all these things. It is simple, clear, and compassionate. This is the guidance we should be seeking. Your counsel and wisdom is meaningful. Your gift of words, a blessing for our community. Thank you.

Alicia, you do downtown historical walking tours?! Where do I sign up? I had no idea.

Bill