A Reality Check for Revitalization

If “downtown activation” is truly the goal, the City of Reno needs to reimagine its own underperforming facilities

Happy August to all. Be sure to check this week’s schedule of City meetings, including the Planning Commission, which meets tonight (August 7). Agendas and other materials are all available on the City’s Current and Upcoming Meetings page here.

I’d like to focus today’s Brief on the topic of activation, that highly prized object of all urban revitalization desires. Activation is that sense of vitality that can only come from the continuous presence of people in a place.

Two meetings I watched last week made me question precisely how the City of Reno is addressing the continued challenge of inactivity in the old downtown casino core—and more specifically, how they’re not.

As the Virginia Street Placemaking Study documented, 70% of Virginia Street through the downtown core is inactive, the result of multiple block-length casino walls with few entrances, empty public plazas, parking garages, and vacant lots and storefronts.

And of course, it’s not just Virginia Street. A vast swath of the city center east and west of the Reno Arch is inactive most of the time. When you factor in Jacobs Entertainment’s ever-expanding parkingpalooza over on the west side, that band of urban dysfunction runs right through the center of town, practically all the way from the Glow Plaza to Greater Nevada Field.

The zoning code calls much of this the “Entertainment District,” but that’s really a misnomer. There is entertainment all over the city; this area doesn’t have a monopoly on that. It would be more accurate to call it a “special events” district, dominated by spaces that are active when something is scheduled there—a baseball game, a bowling tournament, a roller skating party, a concert, a convention, a haunted house—but empty and still when they’re not, which statistically speaking is most of the time. And that’s a problem. There’s a reason, after all, that fairgrounds are traditionally located on the edges of town—when the crowds disperse, their emptiness poses no ongoing detriment. Not so when that void is smack dab in the city center.

The resort casinos of The ROW and the J Resort may be busy little hives of activity inside, but the days when tourists buzzed up and down Virginia Street from casino to club to showroom are long gone and The ROW’s own slogan “the city within a city” is an apt reflection of its “we have everything you need right here” mentality.

When you have a relatively small urban area dominated by insular resort casinos and spaces that rely on a steady stream of programming to generate visible activity, the strategy to secure more activation might seem clear: program more special events. After all, events bring motion to a normally inactive space. A critical mass of people brought together for a shared experience can bring an exhilarating but temporary surge of energy, and for a short time things feel bustling, dynamic, and safe.

There’s nothing particularly wrong or unusual about that strategy. Every city strives to populate its downtown with special events when weather allows. And this summer, Reno has plunged headfirst into special event mode. You can’t watch the new downtown status updates presented to City Council each month without marveling at the sheer amount of time and energy devoted to activating a very small segment of downtown space through programmed activities (as part of its “Activation Pilot Program,” the City has initiated more than 20 events on its downtown plazas alone).

A second downtown revitalization strategy clearly being championed by the city is the attempt to attract and nurture private investment. In truth, this has been a focus for years now. You might recall this video from 2021 in which Mayor Schieve says, “We want to work with great developers with great vision, but the city cannot afford to pay for that and that’s how you do create a quality of life. They’re called private-public partnerships, and those are essential.”

The approach here is, apparently, to foreground the City’s own lack of funds in hopes of attracting monetary infusions from elsewhere. The unexpected windfall of ARPA funds has been one recent source, supplying millions of dollars that the City has dedicated in part to revitalization efforts—not just City-sponsored special events and various commissioned plans, reports, and initiatives (Lear Theater, Truckee River, Virginia Street Placemaking), but also to “ReStore” grants for interior and exterior improvements for some centrally-located private businesses, as outlined on the City’s Economic Development webpage.

At the same time, we have similar initiatives being pursued by the Downtown Reno Partnership, which recently produced a 2023 “State of Downtown” report that actually looks more like an EDAWN marketing package, highlighting institutions, attractions, and amenities found within a one-mile radius of the Reno Arch (Dickerson Road? Wells Avenue? The Renown Medical Center?) rather than providing a baseline of comparison for the area within its actual jurisdiction. If you read through it, you’d be hard-pressed to understand that there are casinos anywhere in the vicinity.

In any case, it’s safe to say that the activation-oriented strategies of producing special events and wooing private investment are humming away.

What we aren’t hearing about—and haven’t heard about in a very long time—is what the City is planning to do to leverage its own properties—of which there are a considerable number in this central area—in the pursuit of permanent activation.

And that’s a problem. The full extent of that problem becomes crystal clear when you watch the proceedings of the Capital Projects Surcharge Advisory Committee, as I’ve been doing for more than a year now. This committee sings one constant refrain: they’re running out of dough, and as a result, the City will soon be unable to fund the upkeep of its own downtown facilities like the National Bowling Stadium and Reno Events Center, since funds from the special mechanism (the surcharge) created just for them by the 2011 state legislature will be practically depleted by 2028.

I watched last week’s meeting of this committee online with Mike Van Houten of Downtown Makeover, who wrote up a great report about it here, so please read that for some background and specifics on that committee, those numbers, and that fee.

As we noted, the solutions this committee has discussed follow one line: charge visitors more, either by raising the surcharge on rooms at The ROW and J Resort (which those properties don’t want to do) or persuading more downtown hotels to add that surcharge to their own rooms (which seems unlikely). For her part, Mayor Schieve seems to want the RSCVA to keep pouring funds that they receive from other room taxes into these facilities, but I’ll get to the RSCVA’s role in a bit.

What I see here is a lot of passing the buck—to visitors, to the casinos, to other hotels, to the RSCVA. What I don’t see is an acknowledgment of the actual problem: that these properties, which were specifically envisioned and constructed to be self-sustaining catalysts for downtown revitalization, are failing in that mission. And they have been failing us in some cases for decades.

You can of course keep raising or expanding that surcharge fee to support their escalating maintenance needs until someone yells uncle. But like the scheduling of endless special events to resuscitate languishing public spaces, that’s just another temporary lifeline, the iron lung of urban development. The goal of revitalization—its holy grail and the sign of its ultimate success—is permanent, self-sustaining activation, infusing places with the ability to thrive on their own.

So why aren’t we discussing what the City itself can do to create a realistic, long-term plan to leverage these properties as major players in the activation of the downtown core?

Let’s call it Reno’s “Physician, heal thyself” moment.

What’s particularly frustrating is that we’ve actually been in this moment for a very long time. The failure of these facilities to do what they were intended to do isn’t news. But in some ways, the City has not just failed to come up with a strategy to fix the situation, but in some respects has actually drifted backwards, making these places more and more dependent on ongoing life support rather than less.

I’d like to explain what I mean by providing a little historical context, to help illuminate how we got here and hopefully inspire our City leadership—and all of us—to consider how to turn the tide.

The National Bowling Stadium

The National Bowling Stadium opened in 1995, but in truth its roots go all the way back to the 1960s, when local leaders decided to locate the primary Convention Center way down on South Virginia Street. Not surprisingly, that was not where downtown’s business and casino interests wanted it to be, but in exchange for allowing it to be established miles away, they received the Pioneer Theater-Auditorium (now the Pioneer Center for the Performing Arts), which was originally a county-owned theater with convention facilities on its lower floor. Recall that this was back when the casinos didn’t have their own convention facilities like they do today—so proximity to a civic convention space was a valuable commodity.

The Pioneer became its own independent nonprofit organization decades ago, but the whole question of where in Reno to locate tourist-oriented public facilities, and how to fund them, has been dogged by that whole quid pro quo mentality ever since.

By 1990, California’s tribal casinos were already eating away at Reno’s drive-up market share, Las Vegas had just kicked off its megaresort era with the opening of The Mirage (R.I.P.), and several of Reno’s downtown casinos had already closed. The City had founded its Redevelopment Agency in the early 1980s, but its initial redevelopment plan wasn’t much more than a list of projects.

Needless to say, the City and its downtown casino interests were keen to diversify the tourist draw, generate more downtown activity, and try to remain a relevant and popular gaming destination (something that Eldorado Resorts and Circus Circus were banking on when jointly opening the Silver Legacy in 1995).

Reno was already attracting some major bowling tournaments at the Convention Center down on South Virginia Street, but its leaders determined that a state-of-the art, purpose-built venue could bring national bowling tournaments to the city on a regular basis. An initial report generated in 1990 suggested that such a facility, if supported by room taxes, could easily generate enough revenue to break even.

Several sites were considered, but the downtown hotel casinos got the National Bowling Stadium located in their neighborhood by approving a one percent room tax increase authorized by the 1991 legislature to directly fund it. That revenue was collected by the RSCVA, which financed the venue’s construction, while Reno’s Redevelopment Agency contributed about $5 million to purchase the land. Ownership of the venue remained with the RSCVA. The catch was that the RSCVA would have to secure commitments from two major bowling organizations to hold national tournaments there and that local authorities would have to develop a major tournament of their own. Also central to the City’s support was the assurance that the facility could be used for other sporting events such as boxing when there was no bowling in town. Put a pin in that last point for a moment.

The plan to construct the facility generated enormous excitement. It would, leaders said, “revitalize an entire block of the downtown area all by itself” since “the surrounding area will also be revitalized with businesses catering to the bowlers.” Reno Redevelopment Agency Director Mary Ann Johnson called it “the lynchpin of our overall revitalization plan” while RSCVA director Jay Milligan said, “We look at the facility as a catalyst that will help attract more high-quality things to the entertainment core.” Boosters crowed that Reno would be crammed with bowlers for at least five months two out of three years, possibly year-round, and become known as the nation’s bowling headquarters.

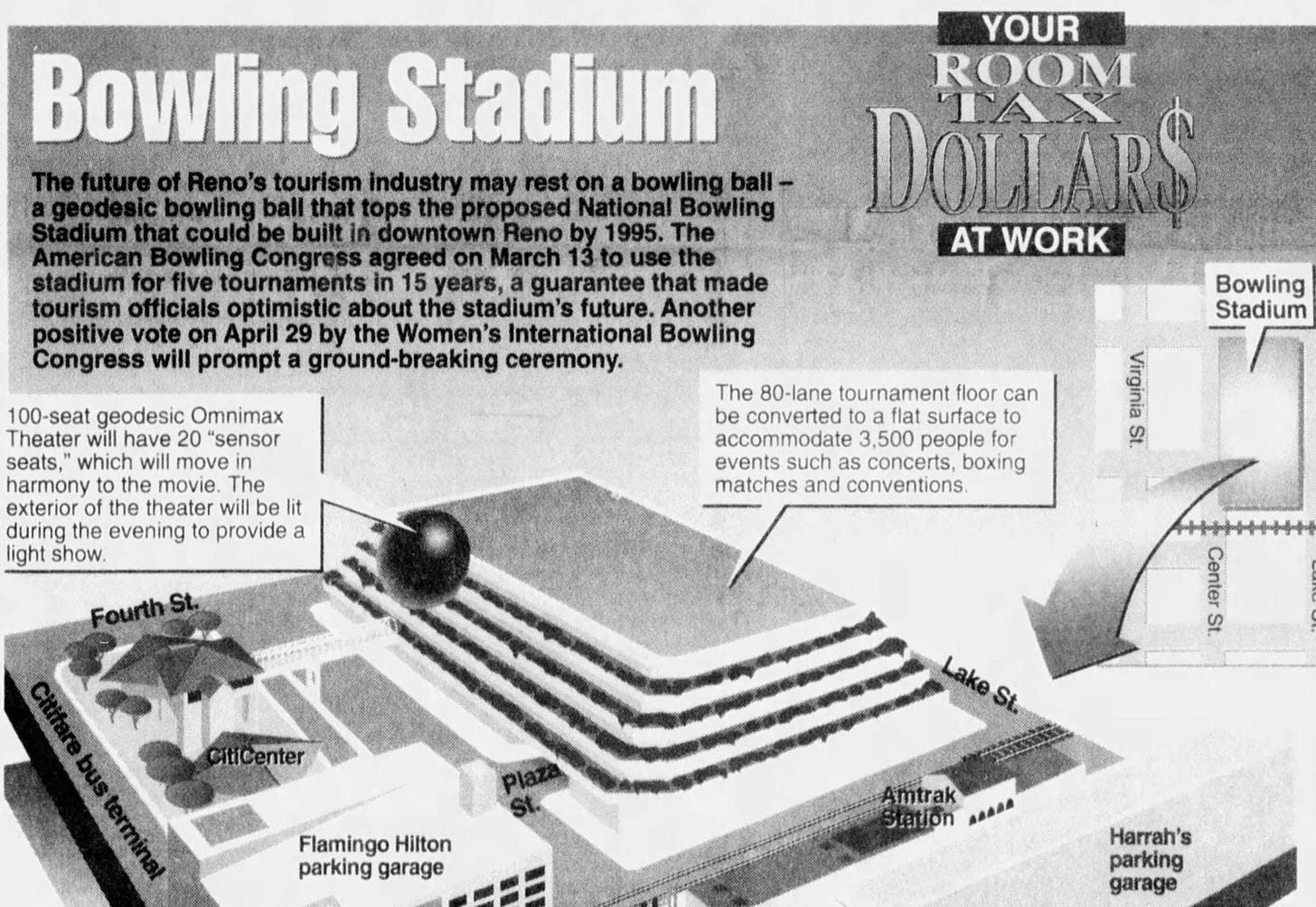

As plans for the stadium developed, so did the assurance that the building would attract much more than bowlers. The tournament floor would be capable of conversion to a flat surface “to accommodate 3,500 people for events such as concerts, boxing matches, and conventions.” That feature wasn’t ready when the approximately $48 million facility opened, but many other amenities were (or would soon be):

A 250-seat, 24-hour, 1940s-style restaurant called Ruby’s Diner, featuring a 100-seat cocktail lounge and booths to accommodate five-person bowling teams and five of their guests. The RSCVA made a $2.5M investment in the restaurant, which was part of a popular chain, expecting to recoup the cost in 7-8 years.

Three sizeable retail spaces, one filled upon the grand opening by Pendleton Woolen Mills.

A tourist information booth.

A pro shop at the building’s front with a functioning lane to try out equipment.

An 170-seat Omnimax theater inside the geodesic dome. The theater was originally supposed to feature “motion seats” but that idea was scrapped in order to expand the seating capacity and to avoid giving bowlers problems with their equilibrium. The RSCVA spent $1.5M to shoot promotional films about the Reno-Tahoe region to be shown there.

Space for a police substation to include a front desk, misdemeanor complaint investigation unit, and stalls for mounted horses to rest and get water. Incomplete at the time of the building’s opening, the substation opened soon thereafter.

A 24-hour public parking garage on the first three floors with around 300 spaces.

It all sounded pretty great—bowling, the ability to house other sports and events, a big restaurant, retail, a theater, and more. So what happened?

It started losing money, almost immediately. Rather than inspiring more development around it, the facility couldn’t even support its own tenants.

Ruby’s Diner closed in November 1996 after struggling to attract patrons. That restaurant space was filled over the following years by a number of eateries and nightclubs—the Big City Stadium Diner & Lounge, Paul Revere’s Kicks, Downtown Cue & Cushion, Bully’s Sports Bar & Grill, and Club 300. Every one of them did well when the bowlers were in town and suffered when they weren’t. Eventually, the exterior door leading into the space from Center Street was removed and while there’s still a restaurant space inside, it’s now called the Kingpin Club and has to be privately booked and rented.

The theater was used for a while, showing films about Mount Everest, Egypt, and wildfires. But the costs of film royalties, advertising, and other expenses was about equal to revenues. I’m honestly not sure if it’s even functional any more (one source says it closed in 2017), and if it is, it’s not open to the public.

The police substation closed in 2011, when 100 City employees were laid off.

The retail spaces never took off and were eventually removed.

The south end of the stadium building remained (and remains) unfinished, although it was estimated that completing it could produce about 40,000 square feet of office space spread over two floors, and in 2017 it was being explored as a possible site for a neon museum. Today it’s fenced in and used for outdoor storage.

Perhaps most disappointingly (and most financially disastrous) it was determined in 1999 that a temporary multi-use floor that could cover the bowling lanes when not in use, in order to host other types of events “appears structurally, economically and operationally impractical to install and remove,” and as a result, the RSCVA said they would focus on maximizing the use of the building as designed, and suggested that if they couldn’t generate more usage, they could always take out the lanes and use it as a second convention center.

That was a huge blow. Of course, the facility wasn’t a total loss. Despite the fact that it had lost money every year since it opened, it was attracting bowlers who stayed in Reno hotels, bought meals, gambled, and sought out other entertainment while here.

But it wasn’t the multipurpose facility that it was originally intended to be, and downtown interests wanted more. By 1999, the city’s largest hotel casinos banded together to support SB 477, which increased the downtown Reno room tax by 2 percent in order to help fund a $105 million expansion of the Convention Center on South Virginia Street and also provided seed money to support some kind of project to help revitalize downtown, another example of quid pro quo at work. Downtown was struggling; casinos were closing every year and the City was in talks with developer David Cordish about some kind of game-changing retail and entertainment complex that could transform downtown (the newspaper referred to him as Reno’s “savior”).

The downtown facility eventually pushed by the Eldorado, Silver Legacy, Circus Circus, and Harrah’s (who had collectively formed an entity called Newco) was an Events Center, to be located just across Fourth Street from the Bowling Stadium. Their argument was that together, the two facilities could attract even more conventions and events, serving, again, as a catalyst to spur the long-promised downtown revitalization that the Bowling Stadium had failed to deliver. An initial idea, later abandoned, was for the four casinos to help fund and then run it.

Downtown Event Space, Take Two

The plan to build the new “world class” Events Center ultimately was approved as a two-prong effort that would involve simultaneously retrofitting the Bowling Stadium into a true multi-purpose facility. The stadium was at that time dark for 18 out of every 36 months, and key to its renovation was—finally—the ability to change out the bowling lanes for a ballroom floor that could allow for full, year-round use of the building’s central space even when no bowling tournaments were in town.

Reno’s Redevelopment staff made it clear that everything hinged on that new ballroom; without it, the project could fail. Additionally, the new Events Center could itself host sporting events, concerts, small conventions and trade shows and overflow from larger ones based at the large convention center down south. By this point, the Bowling Stadium had become a huge financial drain on the RSCVA, and the City of Reno agreed to acquire it and take over its debt so the RSCVA could focus solely on marketing the property—which is still the arrangement today.

Then reality hit yet again. As plans for the Events Center proceeded, it became clear that the City couldn’t afford its ambitious design. The new venue was initially to be connected to the Bowling Stadium by a 30-foot-high “sky building” running over 4th Street and filled with meeting rooms. To save money, the City decided to cut the amount of meeting space and the height of the sky building and delay the retrofit of the Bowling Stadium until they could determine how much money they had left.

As it turned out, there wasn’t any. After simplifying the Events Center design, the City decided to scrap the plan to retrofit the National Bowling Stadium with a ballroom floor. Without the capacity to host events in a multi-purpose ballroom, the Bowling Stadium wouldn’t be able to be booked in tandem with the new Events Center for conventions and non-bowling special events, so the skybridge connecting the two buildings was also scrapped, along with the meeting rooms that would have been located inside it. More money was saved by not installing any kitchen facilities.

The $47 million Events Center opened to much fanfare and a concert lineup featuring national acts, but without a ballroom either there or in the National Bowling Stadium, the downtown gaming interests argued that the full marketing plan they had intended for the project simply wouldn’t work. They needed a ballroom, an industrial kitchen, and more meeting room capacity to make the entire complex functional and complete. So even before the Events Center opened, the plan was hatched to build as its “second phase” a stand-alone ballroom and meeting facility with a kitchen. Silver Legacy general manager Gary Carano claimed that a new ballroom facility would make the Events Center “100 percent useful and help build midweek convention business.”

Third time’s the charm?

The location would be the parcel just west of the Events Center, then the site of the City Center Pavilion (not to be confused with the RTC’s old CitiCenter transit site or the currently-stalled Reno City Center project). The Pavilion was a metal, barn-like structure owned by the gaming interests, who would donate the parcel to the City, and then manage and promote the venue. The City and the company would then split any profits, which remains the arrangement today. The City agreed to the deal and the new $25 million venue opened in March 2008 with a reported 28,000 square feet of space adaptable for ballroom or divided meeting rooms, with a banquet-sized kitchen.

And just to finish off the fourth corner of that City-owned intersection, the former CitiCenter transit site was purchased from the RTC by the City in 2008 specifically for purposes of redevelopment. You may recall that the City issued a Request for Interest for the adaptive reuse or redevelopment of the site back in 2019, and selected a proposal from the developer P3, which would have incorporated the Bowling Stadium and Events Center as well (you can read about it here). But that plan evaporated, and the site is currently being leased by the Downtown Reno Partnership, with no apparent plans for the City to again offer it up for sale or development.

So what now?

Those who supported the construction of these facilities clearly believed at the time that the debt the City/Redevelopment Agency had to assume to finance them would all come back in the form of revitalization, room taxes, and general prosperity. But things didn’t quite work out that way, and today, these four City-owned properties—the National Bowling Stadium, Events Center, Reno Ballroom, and the CitiCenter transit site—have instead, in many ways, become part of the problem.

The City may own these venues but it’s a constant hustle for the RSCVA to program the Events Center and National Bowling Stadium. There’s a lot of competition out there. When it comes to bowling, Las Vegas and Reno still regularly host national tournaments, but other markets like Greenville, South Carolina are getting into the action. The major tournaments not only cost a lot of money to bring to town, but they require constant upgrades that the City has struggled to complete in time.

There’s also a lot of competition within town for any kind of special event, concert, or small convention that might populate the downtown Events Center. These days, Circus Circus, the Eldorado, and the Silver Legacy all have their own convention facilities and meeting spaces. Even the J Resort has meeting rooms, and if Jeff Jacobs is to be believed, their Master Plan (which I’m sure will be revealed any day now) will include their own plans for convention facilities. Concert venues in all those resorts obviously range from the Glow Plaza to the Eldorado’s showroom and the Silver Legacy’s Grande Exposition Hall. And that doesn’t even take into account the other venues and facilities available throughout the rest of downtown and citywide.

At the end of the day, it all comes down to what you think City-owned properties should do. If they were making money hand over fist, their current configurations might be justifiable. The downtown hotels certainly stand to profit from any event scheduled in them—especially those that attract out-of-town visitors—and they obviously don’t directly suffer from their failure to spur revitalization around them.

But the City and its residents need them to do more. Downtown visitors and surrounding businesses need them to do more. The old CitiCenter site needs to developed as originally intended. Perhaps then the Downtown Reno Partnership could move into one of the inactive spaces in the Bowling Stadium or elsewhere. But some component of these buildings needs to be open to the public on a daily basis. Could an entity like the Nevada Historical Society relocate in one of them? That venerable institution had plans several years ago to move downtown from the north side of campus. What about needed services for downtown’s residents? The Visitor Center currently housed in the Parking Gallery on Sierra Street? Something else?

We need to use our collective imaginations to re-envision what these properties can be and do, and generate realistic activation plans that will allow them to thrive. And all of that needs to be discussed in an appropriate forum—not just in an obscure committee with three Councilmembers and casino executives, or in City Council meetings where discussions are governed by rounds of self-imposed three-minute time limits, or by the Downtown Reno Partnership, or the RSCVA board, of which Mayor Schieve was recently elected chair. Again, I will reiterate that the forum for this discussion is the Redevelopment Agency Advisory Board, which the City quietly dissolved about six years ago. We can start with a dedicated Redevelopment Agency Board workshop. But give us a place to talk about these facilities openly and at length.

A Final Word on Facing Reality

I’ll end today with a little anecdote that illustrates the importance of being honest with ourselves and others about these properties and the state of downtown. Every year, City Council has to approve the marketing plan, budget, and capital improvement schedule for the Downtown Ballroom for the following year. As you recall, that responsibility lies with the Downtown Management Co., and it’s a rare opportunity for the public to see and hear representatives of Caesars Entertainment at City Hall. They last visited for this purpose this past February 14th, and my research for this Brief led me to watch that particular item for the first time. Hoo boy.

I encourage you to watch the whole item if you can (it starts here), but I’ll just draw your attention to a few moments. For background, an article had just been published in the New York Times Business section by reporter Ken Belson. The article was called “Leaving Las Vegas to High Rollers, Some 49ers Fans Chose Reno.” (I’ve shared it as a gift article there, so please give it a read.)

In advance of his visit, Belson contacted me, as many reporters do, and I offered to show him around. I met him at the downtown hotel where he was staying, he bought me lunch at The Depot on East 4th Street, and we walked around downtown literally for hours. He saw everything—the new, the old, the good, the bad. We went inside the Silver Legacy, the historic downtown Post Office, the Patagonia outlet. It was a terrific walk and a smart conversation. He also spent time in MidTown and at the Grand Sierra Resort. That’s important.

I didn’t know how much he was going to write about downtown, if anything, but it ended up being a really wide-ranging piece with some history as well as descriptions of what he had seen. He wrote about the divorce trade and The Misfits, he wrote about the city’s big pivot to attract companies like Apple and Tesla. And of the city center, he wrote, “Many casinos have shut or merged. Downtown is pockmarked by open lots….Reno seems forever at a crossroads….Motels and casinos have been knocked down to make way for redevelopment that has barely begun. Last year, an overhaul of the old Harrah’s Reno hotel and casino stalled, leaving a giant eyesore. Many of the remaining casinos are windowless, self-contained bubbles that have turned the surrounding streets into uninviting walkways.”

And he quoted something I had said along the way: “Downtown is at war with itself, battling the needs of the casinos for parking and open space geared toward tourists versus residential mixed-use density….We’re trying to establish a sense of place.”

So this article had just hit, and in her remarks about the Ballroom, Ward One Councilmember Jenny Brekhus, who starts talking on the recording here, brought up Belson’s crossroads quote by way of reinforcing her own concerns about all of these City-owned properties, stating that in her mind they all represent missed opportunities that are not living up to their potential, and that downtown is not performing as it needs to be. (The massive resources that the City and the DRP are dedicating to revitalization efforts in this small area also bear that out.)

Brekhus pointed out that the City is still paying off massive debt on all three of these facilities (she stated that they all tap the general fund, of which I’m not sure, but the debt is real), and with the City’s agreement with the management organization for the ballroom expiring in 2028, said this is an opportune time to consider whether it should be rethought. She also reiterated her oft-expressed point that UNR needs to start investing in Reno’s downtown, obviously meaning south of Interstate 80.

Caesars Entertainment Senior Vice President Ken Ostempowski, who had remained at the podium after his initial remarks, clarified that while the ballroom is an “extension of their facility,” anyone can book it. And then he said this: “One quick comment on that New York Times article. That was a paid advertisement, so for those who purchased that paid advertisement, they had the input on that.” The Mayor nodded and said, “Yeah, I did see that,” to which Mr. Ostempowski repeated, “It was not an independent article. It was a paid advertisement.”

The Mayor laughed and said “Exactly.” Ward Five Councilmember Kathleen Taylor then chimed in, saying, “As the Councilmember for downtown [part of it, anyway], I just want to maybe get rid of some of the misinformation that we just heard, and I think that I heard that you guys had a fantastic weekend with the Super Bowl downtown, and we are doing so much for downtown in the last year and a half. I’m super supportive of this Council and the team that we have put together, and everything that is coming downtown, so that paid advertisement was absolutely incorrect and wrong.” Mr. Ostempowski said, “I concur,” and went on to explain what a record year Caesars had in 2023 and that they sold out all of their venues [for the Super Bowl?], which, hey, good for them, but the article never said that they didn’t.

So here’s the thing. I get that some people don’t like coverage that they feel does not shine a positive light on them or on downtown. Some don’t like that I’m not a breathless promoter of everything the City does. But I’m not in the hype business; I’m an educator, an explainer, and an analyst. I love this city and it’s my purpose and pleasure to help people understand what they are seeing in front of them—and what they’re not—and to try to help all of us make better decisions for the greater good.

New York Times reporters are in the news business. And this reporter spent hours walking around the City, asking questions, and writing honestly about what he saw.

Did Mr. Ostempowski genuinely believe that an article published in the New York Times Business section was in fact bought and paid for, violating that newspaper’s strict ethical code and readers’ trust? Or was he just trying use his position and power to discredit an article that prominently featured a competitor’s establishment and painted an honest picture of the area surrounding the resort he works for?

It might gain a person political or financial points to discredit and defame those they don’t agree with, or who say things they don’t like. It’s easy to claim that critical analysis is the easy road (politicians and PR folks seem especially fond of that Theodore Roosevelt quote that includes the line “It is not the critic who counts”). It’s also easy to stick with the status quo, even when something is clearly not working.

What’s difficult is taking a hard look at yourself, acknowledging that it’s time to stop blaming others for a problem you have yourself, perhaps inadvertently, created, and then taking the steps to fix it. It’s true for people, and it’s true for cities, too.

That’s what I call being real.

I’m out of space today but I’ll be back soon with some updates on prior items. Have a great week, and if you value my writing, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Be sure to check out my Citizen Guide for helpful resources and links for anyone hoping to become more informed and engaged in issues related to urban development (& more) in Reno.

As always, you can view this and prior newsletters on my Substack site, subscribe to receive each new edition in your email inbox, and follow the Brief (and contribute to the ongoing conversation) on X, Facebook & Instagram. If you feel inspired to support my writing and research with a financial contribution, you can sign up for a paid subscription through my Substack site or contribute to my Venmo account at @Dr-Alicia-Barber or via check to Alicia Barber at P.O. Box 11955, Reno, NV 89510. Thanks so much for reading, and have a great week.

Reno has been home for over 30 years now and, while I love the area around Reno, I cannot love a city that cannot do and just doesn't. It does seem that the casino folk like what they have and care not about what the city center is as long as their floors are filled with enough gamblers to lose enough to make owners rich. Downtown Reno is a nothing, nothing to attractive, highly unattractive, concrete canyons as described above. Over the past 30 years downtown has become a dead zone outside. And there is nothing to do for those who do not want to gamble. The response to the NYT's article is pathetic as has been every effort to revitalize, in good part because the powers that be, gaming interests mostly, really do not care about what is beyond casino walls so that what is beyond always looks like shit.

I was a relatively naive 21 year old working downtown in 1991 for the Fitzgeralds group for the Slot Operations president - or whatever his title. “Indian” gaming and its impact was discussed all the time as well as keeping Reno relevant. Like you I have lived through 30 years of “new ideas”. Peter Wilday and the design of the river walk with the purple theme color!!! Cracks me up to hear Devon Reese poo poo that color now - mostly because he is a pompous jerk in general. It is an affliction of getting older how annoying younger people are thinking they know better than people before. And then they just follow down the same old path drinking the kool aid of the latest con person. J Resorts Jeff Jacobs, Gordon Garrett. The whole warehouse industry “diversification” tag team Kazmierski, GOED, city and county, etc. And Reno itself is now generally a ….shit hole to live in.