Happy November to all. Reno City Council will hold their last meeting of the month this Wednesday, November 15th. You can view the entire agenda here, so be sure to read it through for any items of interest, including placing a restroom facility on City Plaza (D.3), policies for sidewalk vendors (E.1), and more.

I’d just like to highlight one. Under item D. 2, Jacobs Entertainment will present a report reviewing its compliance with the Development Agreement they entered into with the City. The agenda has links to the Staff Report, a one-page letter from Jacobs Entertainment, and a copy of the final Development Agreement.

The Purpose of the Review

As a reminder, City Council approved its Development Agreement with Jacobs on October 27, 2021. But it wasn’t recorded with the County until November 2022, which is why the 12-month review is happening more than two years after Council approval.

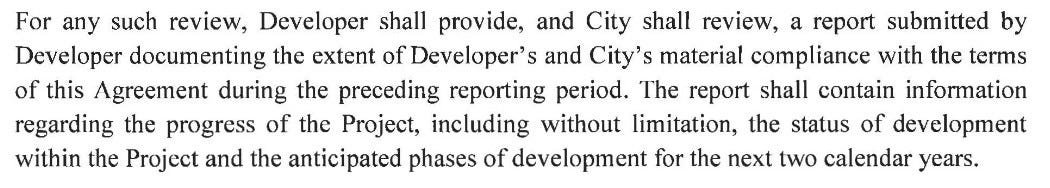

Here’s what’s required this week:

All Jacobs has to do is to demonstrate its compliance with the terms of the Agreement (as well as the City’s compliance with its end of the bargain) and outline their plans for the next two years. Of course, the Agreement doesn’t actually require Jacobs to do much of anything except file a building permit for the condos (now apartments) covered by a separate agreement, so there’s not much to say in terms of their compliance. It’s primarily an opportunity for them to tout what they’ve done since 2021 and announce their plans for the next two years. And two years from now all they will have to do is come back and do the same thing, although they’re not actually required to build anything in that time period (or ever), either.

Will Hindsight be 20/20?

It’s been difficult to know how to write about this item. So much about this Development Agreement was flawed from the outset, from the process and speed by which it was approved, to its deficient content. And I don’t want to repeat myself, so I encourage you to consult my archive of posts if you want more on all that.

Just a quick review for newer readers: as I wrote back in April of 2021 when previewing Jacobs’ initial proposal, this Development Agreement (DA) was the first to come to Council since they overhauled the relevant section of City Code in September of 2020. The Planning Commission had recommended that the City require all DAs to be reviewed by the Planning Commission and to hold a public workshop prior to Council consideration. But Council rejected all of that, establishing themselves as their sole reviewing body.

Seven months after that Code change, Jacobs showed up at Council with a draft agreement (dated January 2021) that its own representative had written. Six months later, they had a signed agreement in hand—no Planning Commission review, no public workshop, not even a Council workshop that would have allowed for more substantive discussion unencumbered by time constraints on every question.

The Development Agreement as approved, with next to nothing up for review, shows the folly of having assumed all that responsibility for themselves.

I could (and have) outlined many of the things that this Agreement failed to do, from my first preview of its contents through Council’s approval of it on October 27, 2021. I repeatedly listed all the requirements that state law allows a Development Agreement to impose on developers. The City incorporated none of them.

Above all, a Development Agreement is supposed to bring clear and stated benefit to both parties. And obviously it’s supposed to describe an actual development. But Jacobs didn’t have to specify what they intended to build in order to qualify for the array of granted fee credit extensions and deferrals. They didn’t have to include a footprint or renderings. They didn’t have to outline phases of development. They didn’t even have to indicate which parcels they were going to build on and which they intended to sell, much less if any would contain affordable or workforce housing.

That’s not how it’s supposed to work. But that’s not the biggest problem here.

Here’s the project description, as stated in the Development Agreement:

Looking through these components, it’s clear that Jacobs Entertainment didn’t need a Development Agreement in order to renovate the Sands. They didn’t need it to erect artwork, demolish dozens of structures on the parcels they bought, or construct an apartment building. They didn’t need it to get the Glow Plaza up and running. They don’t need it to build new conference spaces, a parking garage, restaurants, ballrooms, a pool, or spa. They didn’t even need it to get fee deferrals, incentives, and credits for future construction, which the City regularly hands out to incentivize housing. Sure, those credits including what they secured for “pedestrian amenities” will add up to several million dollars and potentially allow Jacobs to sell the property it has acquired for higher prices. But for a company that’s regularly overpaying for parcels by millions of dollars, I don’t think those were the primary “get” here.

The one thing that the Development Agreement did provide Jacobs that the company wouldn’t be able to secure any other way (because there’s no process to do so) is the one thing that the City was in no position to grant them.

Branding Public Space

Those “area identification” signs and the custom (yet to be installed) streetlights that Jacobs was granted through the Development Agreement aren’t just minor elements of it. They’re the physical manifestation of its most valuable component. It was at the top of the very first draft of the Agreement, which the company (not the City) wrote. It’s the description of “Reno’s Neon Line District®,” and the only change made from the original draft dated January 2021 is that its original southern boundary was originally described as West Third Street rather than West Second.

From the start, this description was highly problematic, and not just because this company seems to have a deeply flawed understanding of what neon is. It’s also problematic because the City allowed Jacobs to include in its description of the “proposed development” an area that Jacobs did not own, does not own, and can never own, because it includes public space that will never be private property.

This brand was center stage in Jacobs Entertainment’s very first presentation to Council, when they slapped a “Reno’s Neon Line District®” logo on the entire Northwest Quadrant of downtown.

As I wrote in “Neon Matters,” that boundary description caused a lot of confusion at the time among various Councilmembers, but their concerns were met with reassurances from Jacobs that it was just a “vision” and not anything “legal,” and later from the City staff that the City had not branded anything. But that’s precisely when that language identifying that entire bounded area as “Reno’s Neon Line District®” should have been taken out of the agreement.

Instead, the City kept that name, those boundaries, and the corresponding signage in the Agreement, along with the categorization of the signs reading “Reno’s Neon Line District®” as “area identification signs.” Doing so seemed to exemplify a bit of circular logic, arguing that these signs would simply be identifying an area—an area they were attempting to create via this very agreement.

The granting of these sign allowances was immediately recognized by the nonprofit organization Scenic Nevada, the region’s experts on state and local sign law, as violations of City Code. And this September, Judge Connie Steinheimer ruled that two of the signs were not in fact “area identification signs” and were therefore prohibited. Her judicial order allowed the archway sign, determining that it was just identifying an area. (You can watch Scenic Nevada attorney Mark Wray’s explanation of what makes that sign a violation as well, from his public comment in the October 25th Council meeting, here.) The City and Jacobs Entertainment have both appealed that ruling to a three-judge panel. And Scenic Nevada has filed a cross-appeal, which you can read about here.

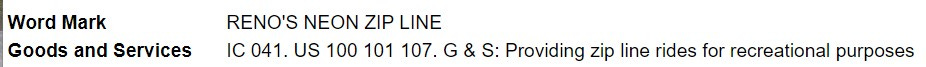

Of course we now know, as I discovered and wrote about last month in “Neon Matters,” that Jacobs had already filed to trademark the phrase “Reno’s Neon Line District®” by the time they drafted the Agreement. You can review that filing here. And that’s not all. Jacobs Entertainment also trademarked the zip line they intend to install on the south side of West 4th Street. Its name? “Reno’s Neon Zip Line.”

“Reno’s Neon Line District®”—like “Reno’s Neon Zip Line®”—is a corporate trademark advertising one company’s gaming, entertainment, and art exhibitions and attractions along one specific “line”—the corridor of West 4th Street. “Reno’s Neon Line District®” isn’t a part of town. It doesn’t identify an area. It’s a corporate brand promoting J Resort and its West 4th Street attractions. And that matters.

I don’t even know how one would begin to calculate the economic value of branding an entire quadrant of a city’s downtown. In aspiration it goes far beyond our local member-based geographic districts or any private development or retail center. In degree of visibility it’s more like the kind of area identification enjoyed by places like San Diego’s Gaslamp Quarter or Seattle’s Pioneer Square. Reno is of course no stranger to street-spanning arches, having practically invented the genre. And various districts in other cities have arches spanning public rights-of-way, like the Fremont East District of Las Vegas or Los Angeles’ Historic Filipinotown.

But “Reno’s Neon Line District®” is nothing like any of those. They are all districts and areas envisioned, designated, and approved by merchant organizations (not single companies) in collaboration with City governments through dedicated, deliberate, and transparent processes. As the Gaslamp Quarter website states, “The Gaslamp Quarter Association was officially chartered in 1982 by the City of San Diego under State Law,” and the “Gaslamp Quarter’s Merchant Association” was decades older than that. Seattle’s Pioneer Square is managed by the nonprofit Alliance for Pioneer Square and the member-driven Pioneer Square Business Improvement Area. And the six blocks of the Fremont East District in Vegas were designated by that City in 2002.

In stark contrast, through this Development Agreement with Jacobs Entertainment, the City of Reno would (attempt to) give those naming rights, that visibility and exposure, that branding power, that level of control, to a single private company.

Placemaking and Place Branding

I was gratified to see some initial discussion about this trademarked brand in the October 25 Council meeting. Mayor Schieve kicked off Council comments with a three-minute explanation of how she views an archway sign with the brand “Reno’s Neon Line District®” as “placemaking identification,” arguing it is no different than the Midtown District. She made similar points several times in this meeting, but she was in the minority, at least among those Councilmembers who spoke about it.

Councilmember Ebert pointed out that an area identification sign would more appropriately identify West 4th Street as the Lincoln Highway rather than a name trademarked by a single company. When Councilmember Duerr said she preferred area identification signs to be more generic and geographically-descriptive in contrast to a trademark representing a specific business, the Mayor jumped in again, saying that the difference is that unlike “The Row” or “Harrah’s,” there isn’t one business named “Reno’s Neon Line District®” and that trademarking is an important act of protection (even though I should point out that no one ever trademarked “Midtown District,” and that’s why anyone can use the word in the name of their business).

Community-based placemaking and place branding are very different than corporate branding, and the Midtown District is a good example of the former. I conducted a Midtown history project for RTC Washoe in 2015-2016 that included oral history interviews with 30 individuals including Mayor Schieve, and with all due respect to the Mayor, the formulation of “Midtown” was nothing like Reno’s Neon Line District®. Is “Reno’s Neon Line District®” a geographical description? Is it a name collectively coined by area property owners and owned by none? No. Is it, perhaps, a longstanding name for the neighborhood? A historical reference? Does it describe an area with a profusion of neon or require its preservation? No. It is and does none of those things. It’s an asset of untold value that would enable Jacobs Entertainment to claim and promote a chunk of downtown including public space for private gain.

Knowledge is Power.

I’ve been an educator since 1995. And my abiding belief that knowledge is power is what drives me to keep encouraging residents and local officials alike to keep reading, keep asking questions, keep synthesizing what we’ve learned over time, keep being open to the possibility of gaining a new perspective. And this moment of review provides us with the perfect opportunity to do that.

So let’s take a step back. At this point, by my calculation, Jacobs Entertainment has acquired close to 100 parcels on the west side of downtown Reno (just search the County Assessor website for parcels owned by Reno Real Estate Development LLC and Reno Property Manager LLC, as well as what’s owned outright by Jacobs Entertainment as JESR LLC. They may own other entities, too.)

These parcels are all located in an Opportunity Zone, one of the areas nominated by Governors and designated by the U.S. Treasury as economically distressed back in 2018. The stated intent of the program was to attract private investors who would finance new projects there in exchange for federal capital gains tax advantages. According to the State of Nevada, “This incentive is expected to generate billions of dollars of investment into low-income areas that have previously not been able to attract reasonable cost of capital to spur economic and community development.”

As Anjeanette Damon wrote in a November 2021 piece for ProPublica, Reno officials included the Northwest Quadrant at the top of the list that they submitted to the Governor for designation as Opportunity Zones, after Jacobs had already begun its property acquisitions. She writes, “Because the benefit is directly proportional to the size of the investment gains, the program tends to discourage projects that won’t generate a large profit. Affordable housing development is not an enterprise that generates large profits.” Neither is investment in the motels that serve as housing of last resort for some of our most economically disadvantaged community members. It might therefore come as no surprise, as Dana Gentry wrote in a March 2022 article for Nevada Current, that “Opportunity Zones, meant to combat blight, spur luxury living” rather than benefiting the lower-income communities where they’re established.

That’s certainly the case here, where Jacobs is methodically removing evidence of the lower-income communities that once called this area home. Clearing the quadrant of motels (and other older buildings) in order to pave the way for some future new investment, no matter how far off, might be a sound strategy for those investing in an Opportunity Zone, but it’s not the greatest PR move, especially during a housing shortage, which helps explain the repeated messaging that the entire area was horribly blighted, that none of the motels were salvageable (except the one Jacobs happened to renovate), that the neighborhood had a terrible reputation, and that because of that poor image, Jacobs had to demolish the corridor’s motels in order to honor its heritage as the Lincoln Highway (Jacobs VP Jonathan Boulware said that last one during a luncheon I attended this past spring).

There are obviously those at City Hall (as in the community) who share Jacobs’ interest in ridding west downtown of what they consider undesirable and underperforming properties in order to pave the way for a bright and shiny yet vaguely conceived new district, who believe that such action might not only increase real estate values and property taxes but turn West 4th Street—as the Mayor and Jeff Jacobs have both said—into “the new Virginia Street.” That’s a vision that they may share but it certainly hasn’t been codified in any official City plan.

Critical thinking demands a degree of detachment, for both residents and our local representatives. In the end, Jacobs is doing what makes sense for his company; that’s what corporations do. And sometimes—often—public and private interests can align. But it’s the job of our representatives to push back when a developer asks for too much, and to understand when that is happening.

In retrospect, perhaps the only Development Project here, the only component that should have been described as such in this Agreement, is the renovation and expansion of the Sands resort. That’s the only part of his expanding real estate empire that Jacobs planned, prioritized, and specifically trademarked as “Reno’s Neon Line District®.” The rest of it is just investment and land speculation punctuated by a few residential properties. The remaining area may someday feature the referenced “2,000 to 3,000 residential units” and an “array” of commercial and retail, or it may not.

So yes, this Development Agreement should have given the City more assurances, but it’s not too late for our representatives to recognize that and take action to fix it.

Making Amends

Why even bring any of this up this week, when all that’s happening on Wednesday is a review? Because I believe that two years out, we can all view this Agreement from a more informed perspective. I believe that the revelation of new information requires focused analysis. I believe that any Development Agreement should be worthy of the City that enters into it. And I believe that the valid concerns raised by Reno residents shouldn’t have been disregarded when this was first pushed through.

I’m sure we’ll hear a lot on Wednesday about what Jacobs has accomplished. We’ll hear about the Glow Plaza and the renovated J Resort. We’ll hear about the ongoing construction of the apartments at Arlington and West 2nd Street. And we’ll likely hear about plans to build a convention center and spa and parking garage and Reno’s Neon Zip Line® with a little commercial cluster at its base. Maybe we’ll hear where and when Jacobs wants to build a new amphitheater. I suspect we’ll hear of their intent to bid on the Bonanza Inn. And who knows, maybe there will be a few surprises, too.

The only action that Council can take is to accept the report. But that doesn’t mean they have to bid Jacobs farewell until 2025. As I noted, there’s more litigation on the way concerning the legality not just of those proposed “Reno’s Neon Line District®” signs but the entire Development Agreement, which could be entirely overturned.

And in the meantime, it’s worth pointing out that according to state law, the Development Agreement can be amended.

What might such an amendment comprise?

It could explicitly list benefits to the community.

It could eliminate the area identification signs altogether (as it may legally have to) and require signs advertising “Reno’s Neon Line District®” to be confined to Jacobs’ private property.

It could include a complete footprint of the “proposed development” depicting which parcels owned by Jacobs would be dedicated to various uses, including resort expansion, commercial/retail, and those “2,000 to 3,000 residential units” listed in the description.

It could require a certain percentage of below-market rate housing on any residential development or some portion of the parcels Jacobs has purchased.

It could require an entity other than the developer to determine whether preservation or relocation of any historic properties in the area is “feasible.”

It could require Arts Commission or Council approval of any replacement of the sculptures that were granted “pedestrian amenity credits” should Jacobs decide to replace them with something else (right now it requires only City staff approval).

At the same time, the City of Reno could consider initiating a process to officially designate and name areas and districts, as Councilmember Duerr recommended and the Mayor agreed, with the Mayor concurring there should be “standards, there’s guidelines, everyone knows what they are, they’re not promoting one particular business,” something I was glad to hear.

On the Subject of Naming

On that note, I want to mention something that most residents and even sitting Councilmembers may not know—that more than three years ago, the City Manager’s office initiated a process to create a new policy to govern the naming or renaming of City streets, parks, and other facilities. Four City Commissions contributed to the formulation of a policy draft to be sent to the City Manager for review and ultimately to City Council for formal adoption. The pandemic wasn’t considered an optimal time to formalize such an important policy, so it was set aside, but it’s time for the City Manager to dig that out (you can read the draft along with the comments I sent to the City Manager’s office about it here). And it might be the proper vehicle to govern the naming of City districts, too.

None of that could happen at this week’s meeting, of course, but that doesn’t mean we can’t ask for it. And if you have questions and comments, now’s your chance to express them. Just reference item D.2 via email at Publiccomment@reno.gov; using the form at Reno.Gov/PublicComment; via voicemail at 775-393-4499; via Zoom using the link on the agenda; or of course by attending in person on Wednesday.

As always, you can view this and prior newsletters on my Substack site, subscribe for free to receive each new edition in your email inbox, and follow the Brief (and contribute to the ongoing conversation) on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram. If you feel inspired to contribute to my efforts, my Venmo account is @Dr-Alicia-Barber and you can mail checks, if you like, to Alicia Barber at P.O. Box 11955, Reno, NV 89510. Thanks so much for reading, and have a great week.

WOW! You're REALLY on top of things here in Reno. We're so fortunate to have you!

Great work. Great perspective. As always.