Fall is in the air, and so it seems are the winds of political change. Not only is campaigning for the upcoming midterm elections in full swing, but the news dropped on Friday that Ward 3 Reno City Councilmember Oscar Delgado has resigned. City Council will hold a special meeting on September 29 to decide whether to replace him via special election or appointment, as they just did when selecting Kathleen Taylor for Ward 5. If you want to weigh in on that decision, Thursday’s agenda is posted here. And if you are so inclined, you may want to refer back to my August 24 post, “Exercise Your Right to Representation,” which lists some of the roles that Councilmembers play in the development sphere, in addition to their many other duties.

Also swirling in the air is talk of Reno’s City Register of Historic Places (the “Register”), which in a broad sense is welcome news. Speaking as a former three-term commissioner (and chair) of Reno’s Historical Resources Commission (HRC), it was long our goal to promote the Register and help increase awareness of what it is, what it does, and why it should be expanded. The specific reason it’s in the news, however, underscores one of my consistent arguments in the Brief: that it is imperative for City projects in specific fields to be undertaken in close consultation with the citizen commissions dedicated to them.

As this latest example demonstrates, such close consultation is not just a courtesy but an absolute necessity in areas where City staff and elected officials simply do not possess the expertise to produce the best (or even a good) result. Let’s discuss.

The “Biggest Little Blockchain”

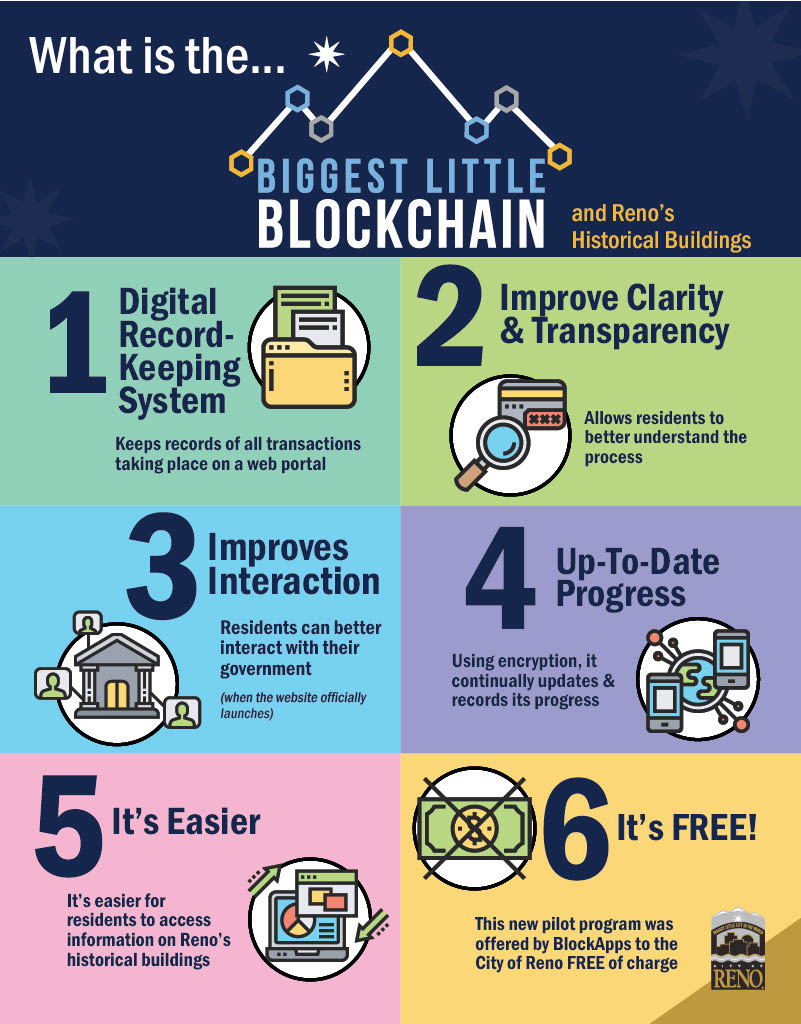

In case you missed it, the City of Reno officially launched the ”Biggest Little Blockchain” with a press release on September 12. The Mayor and City staff touted this new online portal as an innovative way to provide access to information about changes made to the properties listed on Reno’s Historic Register. The platform is a blockchain ledger built by a company called BlockApps, who either offered or agreed to provide the service to the City free of charge (at least for now).

The much-repeated narrative driven by both BlockApps and the City was that the records related to the Register had been contained in old bankers boxes, and that this new portal would finally haul the Register into the 21st century. It would do so by making those records available to the public and staff alike using blockchain technology to create a trustworthy, unalterable record of changes made to the properties via the Certificate of Appropriateness (COA) application process, and thereby promoting governmental transparency, accountability, and accessibility.

The news that the City was putting together an online portal related to the Register came as a surprise when Mayor Schieve first announced it (along with the creation of an NFT of the Space Whale that you can view here) at the U.S. Conference of Mayors event here in June. The City issued its first press release about it (along with the graphic below), BlockApps issued a press release of their own, and the two initiatives were successful in securing coverage from governmental tech-oriented media.

There wasn’t yet anything to see, however. A month later, in a Reno Public Radio piece called “Untangling America’s First City-Backed Blockchain,” the company’s VP of Sales Jeff Powell said, “The City of Reno — which is a very forward-looking entity and is very interested in being a tech hub and driving technology in the city — became interested in exploring what it would be like for them to put some of their municipal records onto the blockchain and make them available to the public.”

Although the idea of using a blockchain ledger for historic property records was news to all but a few, the Mayor’s interest in somehow adopting the technology at the City was not. Back in June of 2021, Wired published “The Mayor of Reno is Betting Big on the Blockchain,” in which Mayor Schieve announced that she had formed a “Blockchain Board on Innovation” consisting of one member, UNR undergrad Theodore Clapp. The Mayor and Clapp were interviewed together for “TezTalks Live” in March of 2021, where they discussed their plans for a whole slew of web3-related initiatives, including blockchain, NFTs, and a Reno DAO. The hour-long interview is well worth watching, since it’s more than I’ve seen the Mayor or anyone else at City Hall say publicly about these technologies, much less plans that are underway.

The City seems to have formally entered into exploration of these technologies sometime last year. The overall sector seems to be the beat of City staffer Ashley Turney, the former Reno City Clerk who was appointed to the newly-created position of “Chief Innovation and Experience Officer” in July of 2021. Together, Turney and Mayor Schieve attended a tech-related conference in Miami sponsored by Blockchain.com this past April, as the Mayor announced on Twitter (below).

I’m not sure why the Historic Register was selected for this initial blockchain-powered project, but there’s no question that the City has long needed to improve its online presence regarding Reno’s historic properties. We’ve wanted the City to simply update its Historic Preservation webpage for years, since it doesn’t even explain how to nominate a property to the Register or feature simple descriptions of the properties listed on it. (The nonprofit Historic Reno Preservation Society does, however, offer a virtual tour of them with information and images on the website Reno Historical.)

So there was some potential here to do a real service by providing more information on the Register properties. But it had to be done right, and as I said repeatedly back in June, it would be crucial for the Historical Resources Commission to be involved in putting this thing together. That’s because the commission has never been staffed by a historic preservation specialist (the City has never created a position for one). Instead, it’s been staffed by a series of City employees, mostly planners, whose primary duties lay elsewhere and who were generally taken off the HRC at some point, or retired or resigned. (The City is currently in the process of hiring a full-time Historic Preservation assistant, so ideally that person will come to the position with some kind of education or experience in the field, although it was not required.)

As a result, it’s the commissioners themselves, past and present, who have largely provided the expertise (many of its members are credentialed as per code) and institutional memory that the constantly revolving cast of well-meaning staff has not been able to provide. But the City never asked any of us for help, and a few weeks ago, we finally got to see what they created. You can view it for yourself here: https://reno.stagingnet.blockapps.net/historicPropertys.

I’m not entirely sure what you’ll find there at this precise moment (despite the claim of being “unalterable,” the portal already has been edited in response to some of our stated concerns), but the main page features a list of building names, addresses, and parcel numbers titled “Historic Property List” (more on that in a minute), with no other explanatory information. Click on a property, and you’ll see a number of fields with various bits of information that I can tell have been copied from the original forms nominating the properties to the Register (although that isn’t indicated), and on the right, a box titled “Certificates of Appropriateness” with a list of project names, applicants, and status. Click on one of the projects and you reach another page with short descriptive information and, if relevant, a date of approval.

The site immediately raised alarms among those of us who have worked with the Register for decades because so much was clearly wrong with the way this information was presented: among other things, denied applications were marked APPROVED; withdrawn applications were marked REJECTED (which is itself the incorrect terminology); applications were listed under the wrong properties and then confusingly marked REJECTED; properties are given incorrect names; applications are listed out of sequential order (despite the fact that blockchain applications ostensibly document consecutive transactions); typos abound; and there are no original records to be seen, despite the City’s claim to be providing access to them.

Even the title given to the webpage—“Historic Property List”—is misleading; any property that’s at least 50 years old is categorized as “historic” (as defined by NRS 381.195 and standard preservation practice). This is not a list of “historic properties” but something much more specific. And several of the properties listed here are not even included on the Register anymore due to demolition, destruction, or relocation. But a user has no way of knowing any of that.

What’s especially perplexing is that rather than simply providing digital copies of the original nomination and application forms (in, say, PDF format), the creators of the portal have entered selected information from them without indicating their source or date. As a result, the property owner info for many is seriously out of date (the owner of the Lear Theater, for instance, is listed as the Theater Community Coalition, an entity that has not existed for more than a decade).

The issuing of a Certificate of Appropriateness rests upon the approval of detailed plans and specifications that show not just that a door was replaced on the El Cortez Hotel, for instance, but precisely how the design of the new door successfully retains the historical integrity of the building’s storefront (the Register generally governs only exterior modifications). The details are the entire point, and often the approved plan differs from the plans as submitted, something that also is not conveyed. Ultimately, the information found in those two bankers boxes, while it makes a great story, was just a fraction of the information related to these properties, representing isolated stages of the nomination and COA process that cannot be understood without knowledge of their context and what they do and do not show.

Upon seeing the site, I immediately contacted City staff, told them of my concerns, and recommended that they take it down for a complete overhaul. Both HRC commissioner Bradley Carlson and I explain why in the This is Reno article “City promotes blockchain tech for its records, experts say effort ‘riddled with errors.’” In that same piece, City staffer Nic Ciccone blames any errors in the portal on the materials themselves, not on staff’s own failure to correctly interpret and describe them, and responds to our concerns by saying, “I’m not aware of any boards or commission being privy to any software being implemented by the city prior to it being implemented.”

It's hard to know how to respond to that. This isn’t a simply a matter of software selection; this is the creation from the ground up of a public-facing portal containing content that was never vetted or verified by those with the knowledge to do so. If the entire point of employing blockchain technology is to establish a permanent and trustworthy record that everyone can be assured is accurate and unaltered, then the paramount concern must be to begin with correct information. I told staff that I’d be happy to help them identify and correct the errors if they involve the Historical Resources Commission in the effort (it shouldn’t just be up to me, after all), but so far have not heard back. The item could easily be added to the HRC’s October agenda.

As I’ve indicated, City Hall is suffering from a significant loss of institutional memory when it comes to its historic preservation programs and policies, which has, I fear, resulted in some serious backsliding in terms of support for these policies and the Commission, and makes it more important than ever for City staffers and elected officials alike to understand them. And despite the contention that the City was under no obligation to consult with the HRC on this project (although I’m not sure why they wouldn’t want to), it’s clear from the City’s own Code that this falls under the Commission’s purview. So let’s take a few minutes to review that code and its contents.

The Role of the Historical Resources Commission

Due to the massive decimation of much of Reno’s historic downtown at the hands of the gaming industry in the 1970s and 1980s, it may come as no surprise to learn that Reno came later than many western communities to integrating historic preservation into its Master Plan and Land Development Code. Indeed, Reno didn’t adopt its first preservation ordinance until 1993 (for reference, Boise and Fresno adopted theirs in 1979, Spokane in 1981, and Las Vegas in 1992). But then Reno started to catch up. In 2006, the City Council worked closely with its Historical Resources Commission to produce its first Historic Plan, which was adopted that year and updated in 2012.

Many of the goals, policies, and actions outlined in that Plan were integrated into the current City Master Plan (beginning on page 82). Concurrently, the Historic Preservation section of Reno’s Land Development Code, chapter 18.07, lays out specific regulations and procedures to support those goals, policies, and actions. Together, the Master Plan, Historic Plan, and Preservation Ordinance provide very clear parameters to guide the City’s approach to historic resources; longtime readers may recall that I referred to some of them last year in a Brief called “Compatibility, Context & Conscience.”

The Historical Resources Commission was created along with the original ordinance in 1993, and Section 18.08.904 of the City’s Land Development Code lays out the many roles they hold with respect to Reno’s historic resources and City actions related to them. There are nine roles in total, and I encourage everyone to read them all, but with respect to this blockchain project, it’s important to cite just a few:

Contribute to the development and review of plans, bylaws, rules, ordinances, regulations, and implementation programs affecting historic resources

Administer on behalf of the city, a register of historic resources to include information concerning historic resources

Advise and assist owners or other persons, entities, or governmental, or private agencies concerned with historic resources

Inform and educate the community concerning historic resources through promotion, signage and wayfinding, publishing information, and by developing interpretive programs and holding events

Present, hear evidence, testify, or assist as appropriate before all boards, commissions, committees, councils, and related public and private entities on any matter affecting historic resources

Were the new blockchain portal simply an internal platform intended for staff use, it might reasonably be considered outside the purview of the HRC, but that’s not the case. The City is specifically touting it as a “public-facing blockchain resident-portal,” clearly intended “to inform and educate the community concerning historic resources.” It seems silly to have to point to the specific language in City Code to justify why the City should consult its own advisory board about their area of specialization, but here we are. So my message to City staff and our elected officials is this: please review the City’s own policies and provide yourselves with the expertise and knowledge that you are not only entitled but obligated to seek out and receive.

There’s a lot more to be said about the role of historic resources in urban revitalization in general and Reno in particular, but I’ll save that for another time. Today my primary message is this: the quest to be recognized as an innovative city should not come at the expense of accuracy and inclusivity.

Clearly the City should (and, moreover, should want to!) collaborate with its Historical Resources Commission about a blockchain-based portal providing information about the City’s Register of Historic Places, just as they should consult with the City’s Arts and Culture Commission when deciding whether to purchase a piece of public art like the Space Whale and create an NFT of it ostensibly to fund more public art in the City. They should similarly consult with other relevant boards and commissions if contemplating the introduction of a Reno DAO and using it to experiment with decentralized land ownership, another idea that the Mayor has floated.

And if this Mayor’s “Blockchain Board on Innovation” still exists, I’d like to suggest that its meetings be made public, to provide a space for residents to learn precisely what new technologies our City staff and elected officials are contemplating adopting, ostensibly on our behalf. We could, for instance, look to a model like Austin, Texas, whose local government recently issued two draft resolutions related to cryptocurrency and Web3 technologies, offering residents the opportunity to comment on the City’s intentions regarding them in a public forum.

Why is all of this so important? Because the decision to pursue technological innovations like these isn’t just an administrative choice; each one of them, when deployed, has real-world, tangible impacts. The types of technological choices under consideration in this new era have implications for our environment and its resources (both natural and manmade), for social justice, for development, for arts and culture, for our city’s financial stability, and more, and as such, they should be approached thoughtfully, transparently, and inclusively. The ”Surprise!” mentality (“Biggest Little Blockchain!” “Skate Park!” “Micromobility Pilot Project!”) may generate short-term headlines, but it’s not the route to securing and retaining either the public trust or quality results. That takes planning, process, and public participation.

I see the City of Reno has announced that residents only have until October 1st to submit comments about the ongoing Micromobility Pilot Project currently installed on sections of N. Virginia Street and Fifth Street, so if you haven’t yet, be sure to do so via the online portal. There have been lots of comments about them on social media, but if you don’t submit them on the official survey, they won’t be taken into account. Analysis of the survey results and other data will apparently be conducted from November through February, so let’s hope that process is as transparent as possible.

As always, you can view this and prior newsletters on my Substack site and follow the Brief (and contribute to the ongoing conversation) on Twitter, Facebook & Instagram. If you feel inspired to contribute to my efforts, my Venmo account is @Dr-Alicia-Barber and you can mail checks, if you like, to Alicia Barber at P.O. Box 11955, Reno, NV 89510. Thanks so much for reading, and have a great week.