Compatibility, Context & Conscience

Creating and protecting places where people love to live

It’s pretty clear to anyone who’s been paying attention that development in Reno has significantly picked up in the past year—both on the outskirts of the city and in established parts of town. After all, that’s one of the reasons I began writing The Barber Brief in the first place—to help provide residents with the tools to participate in the public processes governing that rapid growth.

And while much of that development has been widely and rightfully embraced, the physical aspects of certain projects including their size, specific location, height, and/or arrangement have understandably raised concerns, and sometimes passionate objections, from local residents. This is particularly true for new market-rate multi-story residential developments being proposed for construction in established neighborhoods, whether it’s the project on the former Lakeridge Tennis Club site (6000 Plumas), the townhomes proposed for the Lakeridge Golf Course Driving Range, or the four-story, 34-unit apartment building in the historic Powning Conservation District (more on those last two below).

When it comes to some of the developments lately proposed for Reno in particular, I’ve noticed a few patterns in how some respond to residents’ concerns:

To some, any objections to proposed developments are just NIMBY-ism, that knee-jerk “Not In My Back Yard” reaction attributed to people who would supposedly protest any nearby development they deem objectionable (or who just don’t want anything around them to change, ever).

Others label anyone who raises concerns about proposed housing projects to be socially irresponsible, invoking the region’s serious housing shortage as sufficient reason to support any new residential project out of concern for the greater good.

Still others respond to resident concerns by referring to official City policy, arguing that the prioritization of infill and redevelopment in the City’s Master Plan makes support for any residential infill project not just proper but even mandatory.

It should go without saying that generalizations of any kind should be avoided—in the first case, because casting all objections to development as sheer NIMBY-ism can fail to acknowledge valid concerns about the shape and form (and in many cases, the height) of a specific development project—and with respect to the second, because it’s not entirely clear whether the construction of all types, levels, and price points of housing will indeed help to provide homes to the people who need them most.

But it’s the third type of dismissiveness that I find especially troubling—the insistence that because the city’s Master Plan rightfully encourages infill and redevelopment, any and all infill or redevelopment projects must be supported as proposed, no matter their location or form.

The reason that I find that response so troubling is that Reno’s newly-revised Master Plan does not make such sweeping generalizations, to be universally applied throughout the city. It is, rather, quite specific about what type of infill is suitable—and unsuitable—for certain types of neighborhoods, and in a few cases, for specific neighborhoods. That’s the beauty of a plan that was as thoughtfully and deliberately crafted with as much professional and public input as this one: it emphasizes the importance of context, of understanding this particular place.

Embedded throughout the Master Plan (here) and accompanying Land Development Code (here) is the need to attend to one key determining factor, one critically important component, when considering new infill: COMPATIBILITY.

COMPATIBILITY is the essential quality that helps to ensure that new development will not damage or destroy the character of the places we love. Respect for compatibility protects not only what a place looks like, but how it feels, and how residents and others will connect to, perceive, and experience it.

Attention to compatibility ensures that the terms “housing shortage” and “infill”—both incredibly important—cannot be improperly used as cudgels to justify any kind, size, density, or height of development anywhere, regardless of the context or its visual impact on the surrounding area and on those who live, work, and visit there.

I wanted to focus for a moment on compatibility because it seems to me that many people interpret the word in light of its interpersonal usage, as that ineffable quality that makes two people “fit” together—you can’t define it, but you know it when you feel it. If you carry that notion of compatibility into discussions of urban development, you could understandably conclude that compatibility is entirely subjective, that it’s all in the eyes (or the gut) of the beholder.

When it comes to urban planning, however, compatibility is a very common term that relies upon a clear understanding of the context of a specific area, how that context is physically constituted, why it is valuable, and what is required to maintain it.

Compatibility with the urban landscape—sensitivity to existing context—is what zoning is all about, after all. We’re all familiar with the basic principles of zoning—the fundamental building block of land use that prevents a paper factory from being constructed next to a residential neighborhood, or a prison next to an elementary school.

The type of development that’s spurring such concern in Reno these days, however, isn’t generally about such stark contrasts in use. And it’s absolutely critical to clarify, too, that I’m not talking here about resistance to the construction of multifamily units in affluent neighborhoods of single-family homes—what’s commonly termed “exclusionary zoning.” That may be common elsewhere, and even in Reno on a case-to-case basis, but it’s not the widespread pattern currently underway throughout the city today. The concerns I’m seeing raised about many of the infill projects currently proposed aren’t objecting to the construction of multi-family, multi-story housing in those places, but to the incompatibility or insensitivity of the form, excessive height, or densely packed positioning of the specific developments being proposed for them.

Compatibility in form, determining what “works well” together, is actually a lot more subtle—and at the same time far more complex—than simply “matching” like with like. Calls for compatibility appear throughout the city’s Master Plan, beginning with its initial section about infill and redevelopment, which encourages “targeted infill and redevelopment consistent with the Land Use Plan and the Design Principles for Neighborhoods to expand housing options within established neighborhoods” (p. 42).

Those Design Principles address such components as height, massing, density, and (in certain neighborhoods) community character. They govern the transitions between one kind of land use or building form and another one, to avoid the jarring juxtapositions that might force residents of a row of single-story houses with expansive front yards to suddenly find themselves suddenly living across from, say, a four-story apartment building the width of an entire block, pushed all the way up to the property line.

The area-specific policies outlined in the Master Plan “guide the character and form of development in different locations of Reno and its sphere of influence (SOI)” (p. 97). And they offer clear guidance for retaining compatibility in different categories of places throughout the city.

In the category of Urban Corridors, for instance—central thoroughfares like Virginia Street and Fourth Street—the plan encourages “massing that is appropriate to the surrounding context and sensitive to nearby uses in terms of shadowing, views, and protecting historic context” (p. 124).

In the section on General Neighborhood identity, the plan advocates for transitions, indicating that “Abrupt changes in residential densities should be avoided unless they are part of an integrated plan” (p. 149).

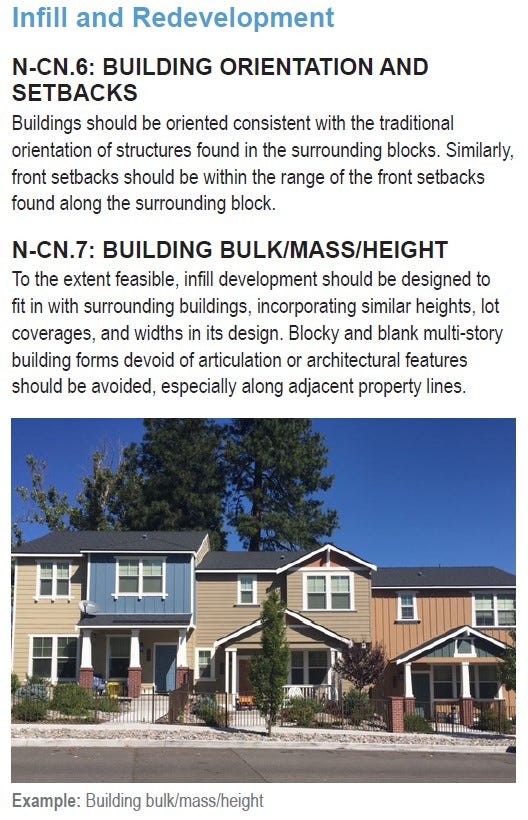

For Central Neighborhoods (within the McCarran loop) the guidelines for “Building Bulk/Mass/Height” indicate that “To the extent feasible, infill development should be designed to fit in with surrounding buildings, incorporating similar heights, lot coverages, and widths in its design” (p. 151).

Those are just a few examples, but you get the picture. These principles are translated in the city’s zoning policy, its Land Development Code, where they regulate such factors as the required depth of setbacks (the distance between a building and the street or sidewalk), the permitted height and width of a new apartment complex, and the number of units it can contain. And when a developer wants to build something that is not allowed by the existing zoning for that parcel, some kind of public review of that proposal is required, so our appointed and elected officials can decide—ideally with respect for the surrounding context and why it’s zoned that way to begin with—whether a change or exception to the code should be made.

Those changes can be in the form of Master Plan and Zoning Map amendments, which permanently redefine the future context of a specific area. On the outskirts of town, that may mean changing a zoning designation from open space to a category that allows housing or mixed uses. In established neighborhoods, Zoning Map amendments might allow the construction of apartments or mixed-use developments in areas previously occupied by single-family homes, estates (Rancharrah), or shopping malls (RED Reno).

Developments can also be granted conditional or special use permits that allow the construction of something that is not necessarily compatible with the existing context, without changing the underlying zoning. Those also require public review, as even one individual nonconforming project can significantly impact how an entire area looks, feels, and functions.

Changing the zoning of an existing parcel or collection of parcels, or allowing for development that deviates from the existing context is a big deal, particularly when it happens in older neighborhoods with an established look and feel. And that’s why the question of compatibility is so crucial—and why pointing out its repeated emphasis in the Master Plan and City Code is something residents should be prepared and willing to do—again and again and again.

Infill and redevelopment are essential components of responsible urban development, and are rightfully encouraged in the city’s Master Plan for promoting walkability, decreasing our reliance on vehicles, increasing our housing stock, and reducing sprawl, among other positive benefits. But infill alone is not a golden ticket that gives developers carte blanche to design as high and wide and crowded together as they want. And they shouldn’t act as though it is.

It’s not especially difficult to design and construct buildings that are compatible with an existing neighborhood, corridor, or district, and to plan projects that don’t cause outrage and heartbreak for the residents who live there, who wish to protect the essential qualities of the places they (and others) love.

It may, however, require a little more imagination and a reprioritization of people over profits to take that place and those people into account. That can mean designing just a little bit lower, building in setbacks from the street, ensuring that adjacent neighbors won’t suddenly find themselves facing a parking garage or multi-story wall. It’s not an all-or-nothing proposition; it’s about sensitivity to context.

At the end of the day, requiring a new development project to be compatible with the surrounding neighborhood, with its most immediate context, isn’t just some touchy-feely plea to play nice, to think about the neighbors, or to have a heart (and conscience). It’s not only an expression of respect for the people who actually live in that place, who will have to deal with the permanent repercussions of thoughtless and incompatible development on a daily basis—although it’s that, too.

Just as importantly, compatibility is a technical requirement that is as firmly embedded in the City’s Master Plan and Land Development Code as any other requirement for new construction, and that deserves just as much adherence and respect as anything else in those policies, not only from the developers who put these projects forward in the first place, but from those elected and appointed officials who are entrusted with reviewing them on the public’s behalf.

And now for a few updates.

700 Riverside Drive

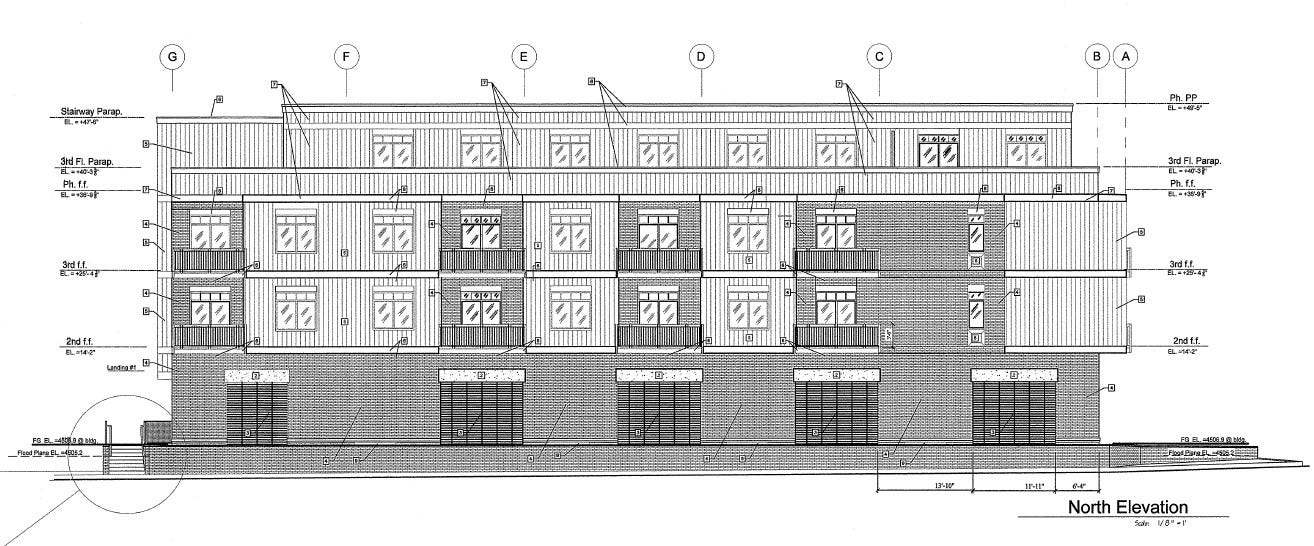

The building permit for the controversial four-story, 34-unit apartment building at 700 Riverside Drive (at Washington Street), in the center of the historic Powning Conservation District, was issued by the City of Reno on March 22, but it has been appealed by neighborhood residents, with a hearing scheduled for May 4th.

I’ve written previously about this apartment building, a project that is problematic for multiple reasons, including its use of Washington Street to add square footage to the building, rather than to set aside private surface parking, the express intent of the City Council when they agreed to abandon this section of street and attach it to this parcel, back in 2006.

The above discussion of compatibility is especially pertinent here. The grandfathering of any development submitted under the previous City Code, and the year-long grace period preceding its full implementation, provides some leeway to private developers to decide for themselves whether or not to respect the stated intent of the new zoning regulations and the compatibility it was written to protect.

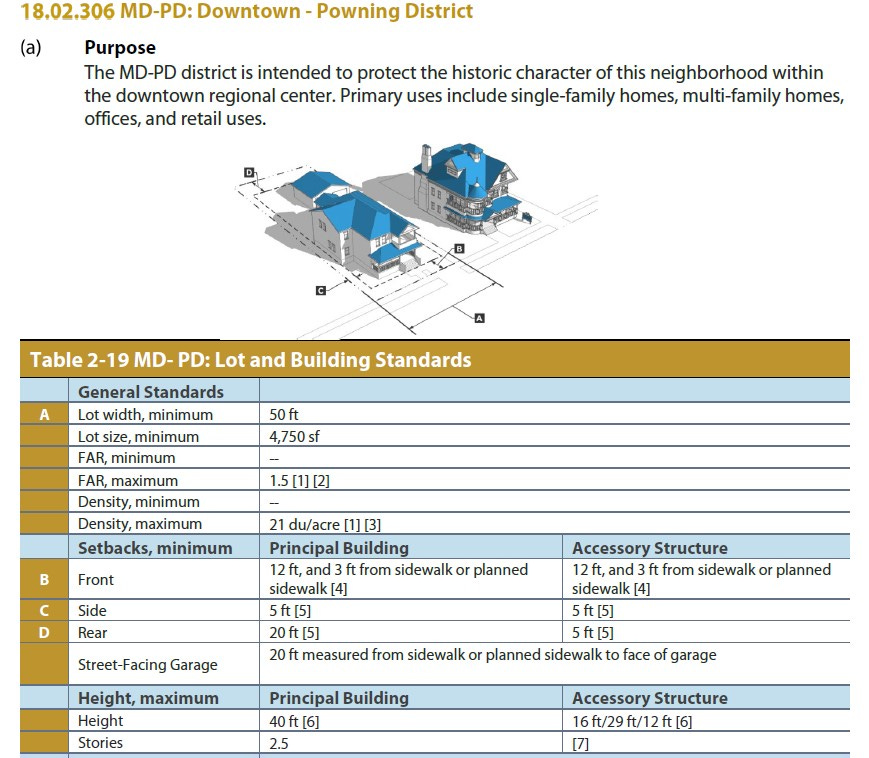

The deliberate choice to not comply with that intent or to respect the neighborhood’s existing character is what makes this 34-unit apartment building so egregiously inappropriate for this particular site. While it could be a wonderful addition to the city in another location, the building as designed completely ignores the Powning District’s established, low-density and low-lying historic context. It isn’t the harbinger of a new, taller, higher-density era for the district. On the contrary, nothing like this building will ever be allowed to be constructed in the neighborhood once adherence to the district’s new zoning code becomes mandatory in January of 2022. A new 2-1/2 story multifamily apartment building with setbacks from the street would (and will) be perfectly fine; a four-story one built up to the property line will not. In this neighborhood, on the pedestrian level, these distinctions make an enormous difference.

The objections (including mine) to the construction of this building don’t come from a place of NIMBY-ism, from a lack of concern for the current housing shortage, or from any personal or ideological opposition to infill. They are motivated, rather, by respect for the City’s own code, a code that was finally adopted after more than a decade of community and City efforts to govern new construction in the Powning District, a code that clearly states that a four-story, 34-unit apartment building in a historically designated neighborhood of mostly one- and two-story single family homes, simply—and irrefutably—does not fit.

The neighbors’ appeal of the building permit for this project is to be heard on May 4th by a hearing officer, not by City Council (unless the ruling by the hearing officer is appealed), but if you were to feel compelled to write to the City Clerk to express your support for their appeal, you can write to CityClerk@reno.gov and reference Case BLD21-00655E regarding 700 Riverside Drive, and consider copying City Manager Doug Thornley at thornleyd@reno.gov and City Council when you do.

6000 Plumas Street

In other news, the proposed condominium complex at 6000 Plumas Street (the former site of the Lakeridge Tennis Club) which I wrote about on March 15th (see here) was approved on March 17 by a 5-2 majority of the Planning Commission. Questions of compatibility with the existing neighborhood were raised here, too. That approval was subsequently appealed by residents to City Council, which is scheduled to hear it on April 28. You can read more about that Planning Commission meeting from KRNV News 4 here, and the appellants have created a website to provide more information on their appeal at www.saveourreno.com.

And now on to some issues to be discussed in public meetings this week.

Planning Commission Meeting on Wednesday, April 7

This Wednesday, the Planning Commission (still meeting virtually) will be reviewing a few development projects, including some I’ve written about before. You can view the complete agenda packet, complete with staff reports, here.

5.3 Lakeridge Place Phase II

This is a proposal to change the zoning of the Lakeridge Golf Course Driving Range from Parks, Greenways, and Open Space (PGOS) to Single-Family Neighborhood (SF) in order to enable the construction of a 46-townhome development called Lakeridge Place Phase II. I wrote about this proposal (and included some maps and images) on March 15th (see here).

This agenda item includes review of applications for a Master Plan amendment, Zoning Map amendment, a tentative map, and special use permits to enable the construction of this project. The recommendation of City staff is to deny all of them, based on their noncompliance with the applicable findings. If you’d like to read through the reasoning and view the full application, click on the staff report here.

5.4 and 5.5 22 on Lakeside

These two items involve a proposal to rezone a three-parcel site on the east side of Lakeside Drive near West Peckham Lane from Single Family Residential (SF-3) to Multifamily Residential (MF-30) in order to enable the construction of 22 single-family attached townhomes on one of the parcels. The rezoning item is under Item 5.4 here and the tentative map and conditional use permits for the project will be reviewed under Item 5.5 here.

As always, if you want to send in public comments on any Planning Commission agenda item (or in general), follow the directions at the top of the agenda here which also includes a link to watch the meeting online, starting at 6:00 p.m. on Wednesday.

Historical Resources Commission meeting on Thursday, April 8

Included on the agenda of items to be discussed by the City of Reno’s Historical Resources Commission in their virtual meeting on April 8th are updates on the following historic buildings:

For more information on how to view the meeting and provide public comment, view the full agenda here.

More Current Development Projects

The March 27 memo from the City of Reno’s Community Development Department containing information about upcoming development projects can be viewed here. Included are projects on North Virginia Street, Moya Boulevard, the Hunter Lake Neighborhood, Mount Limbo Street, and various parcels in the Daybreak development (since renamed Talus Valley). Tentative dates for all public reviews of those projects are included in the memo.

That’s definitely enough for today! As always, you can view my previous newsletters, with more context, analysis, and tips, on my site, https://thebarberbrief.substack.com/. If you’re not yet a subscriber, click the button below to sign up for free. And have a great week!

Alicia, Your blog is just terrific. Thanks for taking the time to provide such a well documented and reasonable presentation.. I hope I get to meet you sometime. Mike Robinson

Hi there! Thank you so much for the information on the 700 Riverside drive project, and the viewpoint you provide. Makes me feel less insane for objecting it.

Question (because I’m having trouble finding more details) - Since the appeal is only being heard by a hearing officer, is my only option to send a letter to council? Want to make sure I exhaust every option. Thanks in advance.